The three worst things about email, and how to fix them

- The Tech Platform

- Aug 10, 2020

- 10 min read

You’ve got (too much) mail! A buzzy new service called Hey isn’t for everyone, but helps us see how we lost control of Gmail, Outlook and Yahoo Mail.

Apologies if you’ve been waiting for an email from me. My Gmail has 17,539 unread messages. Raise your hand if you have even more. For many, Gmail accounts have become less communication space and more of an endless pile Google gets to snoop through. Pandemic life has only made digging through the coupons, Zoom invites, newsletters and school assignments more fraught. A lot of important conversations have shifted to text, WhatsApp, Slack and Facebook, but that hasn’t done away with email … or made not responding any less impolite. Most consumer tech gets better over time. Why doesn’t email? I’ve gotten some perspective on that over the past month by testing a new consumer email service called Hey. It wants us to declare Gmail, Outlook or Yahoo Mail bankruptcy to start over with a new address, radical new organizational ideas — and pay $100 per year for it. Hey attracted 185,000 sign-ups in its first four weeks, and it’s been a moderate success for me. After forwarding my personal Gmail account into Hey, instead of 75 to 100 emails to confront every day, I now get 10 to 20.

But if that $100 price tag doesn’t make it obvious, let me be clear: Hey isn’t for everyone. Most people would rather visit the DMV than change email addresses. And Hey requires significant upfront effort to make use of its organizational system.

Yet Hey still does everyone a favor. Its creators, longtime tech rabble-rousers Basecamp, are calling out some of the root problems with the email we’ve come to tolerate. Hey hasn’t totally cracked it, but it’s a welcome throwback to an era when our digital tools weren’t limited by a few giant corporations driven to mine our personal information.

Here’s the root of our problem: Inboxes have become to-do lists other people get to make. In recent years, we handed over a lot of control to black-box algorithms and advertising companies.

This column isn’t only hate mail for Gmail. Microsoft’s Outlook, which replaced Hotmail, also uses artificial intelligence to organize inboxes in ways that often don’t seem very intelligent. Yahoo Mail, now owned by Verizon Media, has been colonized by data-mining marketing. When I asked to speak with the email product managers at each company about what wasn’t working, all three declined. Google sent me a list of Gmail productivity features, Microsoft answered written questions and Yahoo didn’t reply. That’s hardly how you treat products you’re proud of.

Gmail, with more than 1.5 billion accounts, and Outlook (which Microsoft won’t share numbers on) have used their scale to make important inroads against spam and security threats. But they’ve also focused on serving the lowest common denominator — no wonder most inboxes still just look like endless rows of text. A few start-ups including Hey and the significantly pricier Superhuman are experimenting with new ideas, but there’s a long, sad history of companies trying to shake up email, being bought by Google, Microsoft and other giants … and then shut down.

Here are three of the worst things about email today, the clever ways Hey addresses them and some ways you can perform an inbox intervention. Email is so big, and our needs so diverse, I’d love to hear your ideas, too. We can hope Google, Microsoft and Yahoo borrow some.

One of Hey’s big organizational ideas is that you have to screen each and every sender before their email can get through. (Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

Problem 1: Anybody can email you. And they do.

I remember how revolutionary Gmail felt when it arrived in 2004. It gave you gobs of free storage and fast search so you didn’t have to organize or delete to find things. Hotmail and Yahoo eventually copied the keep-and-search approach.

Since then, the email tide became a tsunami assault on our attention. You can’t search for what you never even see. Every day in 2020, 306 billion business and consumer emails will be sent, according to the Radicati Group — up from 206 billion every day five years ago. Today my inbox is so overstuffed, I pay Google $20 per year for storage rather than clean it.

Hey’s radical solution is that we should put up a velvet rope to our inbox. Every time someone new sends you email on Hey, you have to tap thumbs up or down on whether they get through. Senders have no idea and don’t have to do anything. The ones that don’t get approved go into a special screened-out folder. (Spam gets directed into a separate junk file.)

Cutting out some senders feels good, even if it isn’t 100 percent effective. Farewell, Netflix “Top Suggestions for Geoffrey” email! But it’s also work — even after a month, some days I have to screen out five or more senders. And you can’t ban senders who send both marketing that you don’t need and receipts that you do. Still, my overall email load is a fraction of what it was before.

If this idea appeals to you, consider making a clean break with a new account. (Hey offers a 14-day free trial.) You can hold on to an old one that you check infrequently or direct junky senders to. The people you really care to hear from will learn your new address.

None of the big free providers have a way to make screening mandatory, but there are some tools to help banish unwanted senders:

On Gmail you’ll find a tiny “Unsubscribe” label next to the address of some, but not all, messages that should make future ones stop. Also, in the Web, if you tap the three dots on the top right side of a message, you can tap “Block,” which sends the sender to the spam folder. (Pressing “Mute” just makes that particular conversation thread go away.)

On Outlook there’s also an “Unsubscribe” label next to some messages and a special page (link here) where Microsoft gathers everything it suspects is a “subscription” in one place so you can say bye-bye.

Yahoo Mail makes a “Spam” button easy to get to at the top of the message but buries the “Unsubscribe” option under the three dots at the top right of a message. There you’ll also find a “block” sender, which keeps the sender from making it through at all.

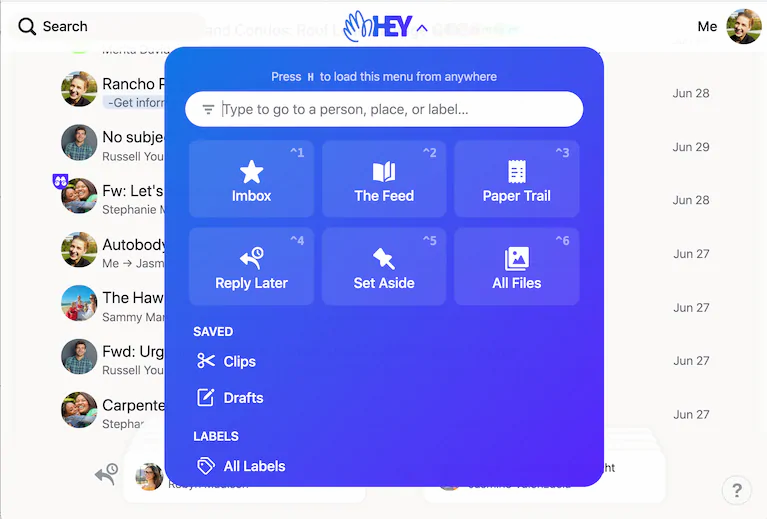

Hey replaces a single inbox with three places your emails can live: The main Inbox for important messages, The Feed for newsletters and marketing mail, and the Paper Trail for receipts and other important matters. (Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

Problem 2: Important stuff gets lost

Some email purists think we need to achieve “inbox zero,” where every message is filed or deleted. That sounds exhausting. Of my 17,539 unread emails, there are probably only a few dozen that I’m really interested in — or, would have been, if I’d seen them. How do we surface the right ones?

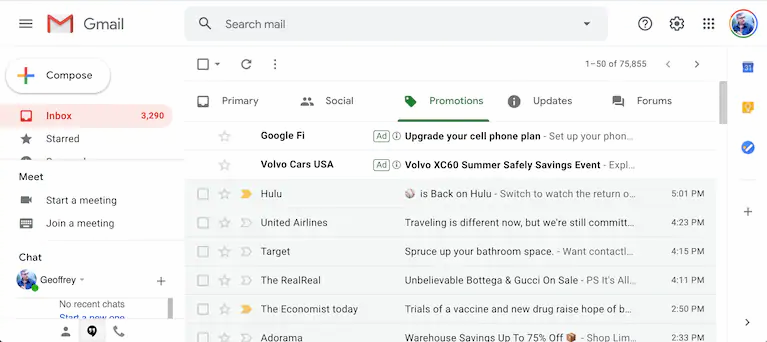

In 2013, Gmail introduced the idea that we should have more than one inbox. Under search in Gmail you’ll see three tabs: Primary, Social and Promotions. Whenever email comes in, Google’s artificial intelligence decides where it should go, like the Sorting Hat at Hogwarts. Since 2018, it will also resurface emails you didn’t respond to but it thinks you should.

Microsoft introduced its own magical sorting to Outlook in 2016 using two inboxes, Focused and Other. (Yahoo’s default is still just one long list.)

In theory, AI can help surface what matters when most people don’t have the time to organize inboxes themselves. In practice, the AI flunks just often enough to make email even more of a mess. My Primary Gmail inbox is still cluttered with stuff I rarely read. (This being Google, the world’s biggest ad company, promotions gets its own default tab, but not newsletters.) And I know tech support folks who find Outlook’s Focused Inbox so unreliable, they make turning it off part of setting new accounts.

Gmail will use artificial intelligence to sort your messages into tabs, visible along the top of your inbox. Primary, Social and Promotions are there by default, but you can add Updates and Forums in settings. (Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

You can try to make their AI smarter. On Gmail, you can turn on additional tabs for Updates and Forums in Settings, and Google says it gets better at sorting when you move messages between the tabs and reply to emails. Microsoft says you can teach Outlook what matters most by moving emails between Focused and Other.

Hey’s solution: Use human intelligence rather than artificial intelligence. It offers three functional inboxes and asks you to screen senders into them, too. Front and center is the Inbox, which only shows messages you haven’t read at the top. (That’s I-M-box, like I-M-portant messages. I’m rolling my eyes, too.) The Feed is where you send all the newsletters and promotions you can scroll through as previews (like on Facebook’s news feed), rather than rows of subject lines. And the Paper Trail is a home for things like receipts and tickets.

Hey’s categories make more sense for the emails I receive, though I still struggled with where to direct those senders who use the same address for everything. “Over time we’ll work out ways to help people deal with senders who use the same email address for good stuff and junk stuff,” Basecamp chief executive Jason Fried told me.

The big free services do offer some tools you can use to sort incoming messages into boxes you define yourself, if you take the time:

Gmail offers a “Filter Messages Like This” option in the three-dot menu at the top of messages, where you chose how to sort by email address or, more helpfully than Hey, even keywords.

Outlook makes it a bit easier with a button labeled “Sweep” at the top of every message. Tap it, then tell it to send that message and all future ones from that sender into a folder. You can also set up “Rules” to redirect messages based on things like words in the email.

Yahoo Mail also has filtering tools available in the three-dot area on top of messages.

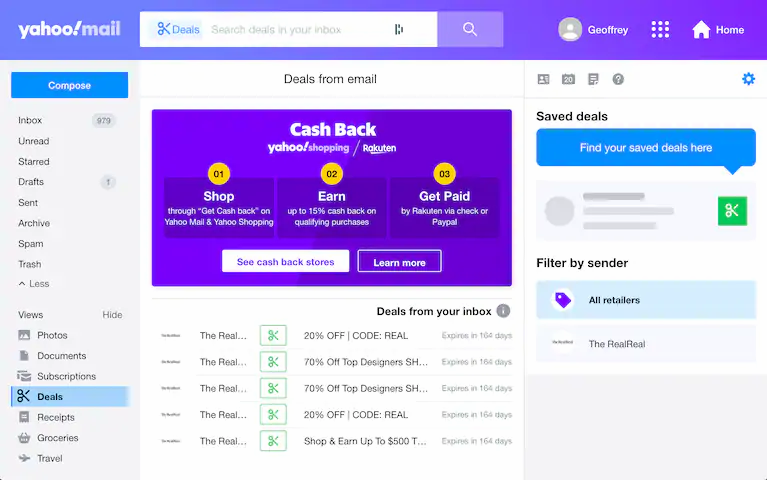

Yahoo Mail is a little too eager to data-mine the contents of your correspondence, like this menu of “Deals from your inbox.” (Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

Problem 3: Your email isn’t really private

Opening someone’s snail mail is a federal offense. Tech companies snooping on our email is not. Yahoo’s privacy policy makes it clear they’re using the contents of your correspondence for ads: It may “share certain analyzed elements of your communications, such as keywords, package tracking and product identification numbers, with third-parties in order to enhance your user experience and personalize your ads and content.” Is anything off-limits? Yahoo didn’t respond to my questions. Yahoo takes away the ads if you pay $3.50 per month for its Pro version.

For most of Gmail’s life, it also used the contents of your messages to target you with ads. In 2017, Google said it would stop doing that and only target Gmail ads based on the giant trove of other personal data it has gathered about you. Microsoft says its ads are also targeted only on broad demographics and anonymized data from search. There’s no way to opt out of ads on Gmail, even if you pay for extra storage. On Outlook, Microsoft takes away the ads if you get a $100-per-year subscription to Office 365. Google and Microsoft also mine your data to train their AI programs, which are growing moneymakers. When they watch us write emails or move between inboxes, we’re the worker bees making their software smarter. Gmail users can take a look at the creepy catalogue Google keeps of things you’ve bought, based on its AI reading your receipts. (When you grant them access, Google also allows outside companies — from price comparison apps to travel planners — to scan your email.)

To be sure, AI lets Gmail and Outlook do some nifty things, such as offering suggestions on how to write emails. But there’s no way to opt out of their data mining. “The assistive experiences people have come to expect and rely on in email are only made possible through the use of AI and machine learning models,” Lynn Ayres, the general manager of Outlook, said in an email.

You have to pay $100 per year for it, but Hey has no advertisements and promises not to mine our correspondence. There are some other privacy-preserving alternatives:

Apple won’t mine or advertise against the contents of your messages in iCloud email accounts, which come with every purchase of an iPhone.

You could switch to an email provider that further encrypts your messages such as ProtonMail, which you have to pay for if you want more than 500 mb of storage.

One more data outrage: Most email services are also complicit in letting marketers and other senders know when, and even where, you open them … and then email you more! Emails can contain hidden trackers that phone home when you load the pictures in messages or click on things.

Hey uses technology to automatically block some trackers by inserting itself in between you and the sneaky pictures, though it doesn’t block the trackers in links. Gmail and Outlook let you block images from loading, but that also cripples some messages.

More than any one privacy practice, the bigger issue is incentives. Yahoo and Google, and to a lesser extent Microsoft, rely on advertisers and data mining to make money. So they’re less inclined to evolve their products in ways that get in the way of marketing or gathering more data.

There’s a lesson for us in that, too. We’ve come to assume email should be free. Turns out we get what we pay for.

The secret life of your data: What you need to know

For all the good we get from technology, it can also take a lot from us. The Washington Post tech columnist Geoffrey A. Fowler examines the personal information streaming out of devices and services we take for granted.

iPhones and Android phones: Hidden trackers in apps share personal information — even while you and your phone are asleep.

Alexa: By default, Amazon keeps a copy of everything Echo smart speakers record.

Credit cards: A half-dozen kinds of companies can grab data about purchases, from your bank to the store where you’re shopping.

TVs: Once every few minutes, smart TVs beam out a snapshot of what’s on your screen.

Cars: Automakers use hundreds of sensors and an always-on Internet connection to record where you go and how you drive.

Web browsers: Google’s Chrome loaded more than 11,000 tracker cookies into our browser — in a single week.

Browser extensions: Add-ons and plug-ins can see and share everything you do on the Web.

Don’t sell my data: The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) can help even residents of other states see and delete their data — and tell companies to stop selling it.

Source: Paper.li

Comments