The making of Mojo, AR contact lenses that give your eyes superpowers

- The Tech Platform

- Feb 13, 2020

- 12 min read

Using a display the size of a grain of sand to project images onto the retina, this startup could help everyone from firefighters to people with poor vision.

When I looked into the user interface of Mojo Vision’s augmented reality contact lenses, I didn’t see anything at first except the real world in front of me. Only when I peeked over toward the periphery did a small yellow weather icon appear. When I examined it more closely, I could see the local temperature, the current weather, and some forecast information. I looked over to the 9 o’clock position and saw a traffic icon that gave way to a frontal graphic showing potential driving routes on a simple map. At 12 o’clock, I found my calendar and to-do information. At the bottom of my view was a simple music controller.

Rather than wearing Mojo’s contact lenses—which aren’t yet ready to demo—I was looking at a mock-up of a future, consumer version of their interface through a VR headset. But the point was made. Instead of offering the pretty holograms of the Magic Leap and HoloLens headsets, Mojo aims to place useful data and imagery over your world—and boost your natural vision—using tech that can barely be seen. The startup named the lenses “Mojo” because it wants to build something that’s like getting superpowers for your eyes.

Mojo’s display is designed to be useful, not flashy. [Photos: courtesy of Mojo]

This audacious idea is part of a much larger trend. In the coming decade, it’s likely that our computing devices will become more personal and reside closer to—or even inside—our bodies. Our eyes are the logical next stop on the journey. Tech giants such as Apple and Facebook are just now trying to build AR glasses that are svelte enough to wear for extended periods. But Mojo is skipping over the glasses idea entirely, opting for the much more daunting goal of fitting the necessary microcomponents into contact lenses.

The company’s been at this since 2015, based on research dating back to 2008. And while it doesn’t expect to bring a finished product to market for another two or three years, some smart people in Silicon Valley venture-capital circles are betting it’ll all work. Mojo Vision has attracted $108 million in venture capital investments from Google’s Gradient Ventures, Stanford’s StartX fund, Khosla Ventures, and New Enterprise Associates (NEA), among others.

Saratoga, Calif.-based Mojo has kept its plans for an AR contact lens under wraps for more than three years. I began meeting with its key executives a year ago, keeping tabs on the evolution of the company’s product and its strategy for bringing it to the world.

Though Mojo still has challenges ahead, it says that it’s already figured out the parts of its creation that might sound, at first blush, most like science fiction. “We’re really confident about this working,” said VP of product and marketing Steve Sinclair, who previously spent seven years at Apple doing product planning for the iPhone. “That’s why we’ve come out of stealth, because we’re seeing all the pieces coming together into a product that does everything we want it to do.”

BAD VISION, BIG IDEA

Mojo Vision was born of the ideas of two men, both Valley veterans who share a deep interest in eye-based tech—and who also both happen to have poor eyesight.

Cofounder and CEO Drew Perkins had already cofounded the optical networking company Infinera, which went public in 2007. He also cofounded and sold three other companies, including a cable network architecture company called Gainspeed. In 2012, when he was Gainspeed’s CEO, he developed cataracts, a common vision ailment where the cornea becomes clouded. Surgery fixed his far-field and near-field vision, but left him with significantly limited midrange vision.

"THERE’S GOT TO BE A WAY TO GIVE PEOPLE ADVANCED OR ELEVATED VISION WITHOUT SURGERY.”

The experience got him thinking about using optical technology to correct vision problems, or even to push a person’s sight beyond 20/20. It also led him to muse about how he was investing his time. On the day Perkins dropped his son off for his first year of college in San Diego, he decided to pivot his professional life toward finding out if the “bionic eye” concept might really be possible. He initiated the sale of Gainspeed (it was eventually bought by Nokia) and took a year off.“

I thought, ‘How can I give people this kind of super-vision?'” he told me. “There’s got to be a way to give people advanced or elevated vision without surgery.” And the entrepreneurial part of his mind began wondering if there might be a way to make money providing such technology.

Perkins didn’t know it at the time, but an ex-Sun Microsystems senior engineer, Michael Deering, had been thinking about some of the same issues. Before leaving Sun in 2001, Deering had built a reputation as an expert in artificial intelligence, computer vision, 3D graphics, and virtual reality. And he too had poor vision. After Sun, Deering spent a decade working out all the problems of focusing a micro-display—either within a contact lens or implanted in the eye—at the retina. Through his research and simulations, he was able to find answers to the most significant problems—work that was reflected in a steady stream of patents since 2008.

For much of that time, Deering had been consulting with ex-Sun CTO Greg Papadopoulos, who was now a venture capitalist at NEA, on ways to make a product and a business out of his work. NEA had also invested in Gainspeed, and when Perkins came to Papadopoulos in October 2015 to talk about the possibilities of the bionic eye concept, Papadopoulos was interested. At the end of the meeting, he told Perkins about Deering. Since there was obviously some potential synchronicity, the three men met.

Drew Perkins (left) and Michael Deering [Photos: courtesy of Mojo]

After Deering explained the work he’d been doing, Perkins felt energized. “I remember saying, ‘Wow, he’s figured it out,'” Perkins says. “He was able to unlock the tech that would need to exist for this to work.” Deering would become Mojo Vision’s chief science officer.

With Deering’s decade of science and Perkins’s experience in building optical technology products, the idea now had the critical mass to become a company. Mike Wiemer, a Stanford PhD who had earlier founded a solar cell company, joined as a third cofounder and CTO.

By the fall of 2015, Perkins, Deering, and Wiemer had validated their idea: “We said, ‘Hey, this could work,'” Perkins says. They incorporated under the name “Tectus,” a moniker they would use while in stealth mode. For the next few months, they fleshed out the business plan. When they presented it to NEA, the firm invested $750,000 in seed money. Perkins put in $750,000 of his own.

Papadopoulos told me that until that point, the whole idea of an eye-mounted LED was mostly theoretical. Deering had worked out the mathematical problems and had done some simulations, but building a real product was another story. It would take some special talents to do that. Perkins says he found the first “couple dozen” recruits at places like Apple, Amazon, HP, and Google. They’d be asked to invent something that had never been built before, using technology that Papadopoulos said would have to be “called in from the future.”

WHAT’S IN THE LENS

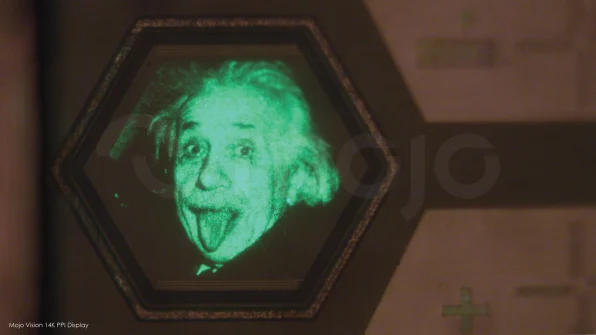

I had no idea that displays not much bigger than a grain of sand even existed. But there it was, under the view of a microscope, displaying an image of Albert Einstein sticking his tongue out at me. Mojo’s newest and smallest display, it squeezes 70,000 pixels into a space that’s less than half a millimeter across.

This display is the centerpiece of the Mojo lens. It’s positioned directly in front of the pupil, so that it projects and focuses light toward a specific area of the retina at the back of the eye. The display is so small and so close that the eye can scarcely see it. At least in the beginning, its quality will be more utilitarian than aesthetically pleasing—you don’t need stunning quality to perform tasks such as display weather information.

Albert Einstein makes a guest appearance on Mojo’s tiny display. [Photo: courtesy of Mojo]

The display focuses its light on a tiny indented area of the retina at the back of the eye called the fovea, which we use to detect the fine details of objects right in front of us. This little indention takes up only about 4% to 5% of the area of the retina, but it contains the vast majority of its nerve endings. It’s thick with photoreceptors that convert light into electrochemical signals, which are then transferred through the optical nerve to various vision centers in the brain. Moving outward from the fovea, the number and density of these photoreceptors decrease rapidly and steadily. We use these lower resolution areas of the retina for our peripheral vision.

All of this ocular science explains why Mojo’s display is practical. It mainlines light directly to the tiny portion of the retina that can see it best. And because there are so many photoreceptors in the fovea, the display needs less power and less light to transmit images.Along with the display, the Mojo lens will contain a supporting cast of microcomponents. The first versions will include a tiny single-core ARM-based processor and an image sensor. Later versions will add an eye-tracking sensor and a communications chip. At first the lenses will be powered by a tiny thin-film, solid-state battery within the lens. Sinclair says the battery is meant to last all day and will charge in a small case that’s something like an AirPods case.

Eventually, the lenses might get their power wirelessly from a thin device that hangs loosely around the neck like a necklace. The lenses will also rely on an internet connection provided by a smartphone or other device for some of their functions, such as sending and receiving data.

PUTTING AR TO WORK

Like any form of augmented reality, what Mojo is working on is only partly about technology. It’s also about finding valuable applications for AR. During a November visit to the company’s offices, I saw something the company is developing for a very specific set of customers: firefighters.

Wearing a VR headset to watch an early prototype demo of this lens experience, I saw a floor plan of the burning building I had just entered. Yellow lines began to form the outlines of tables and chairs within the smoky room. Graphical symbols marked the locations of other firefighters, even when they were separated from me by a wall. Numbers at the top of my view showed my oxygen tank level, communications signal strength, and other data. An alert began flashing, instructing me to get out of the structure.

Steve Sinclair [Photo: courtesy of Mojo]

This AR interface “allows a firefighter to see situational things while they’re holding an axe or a hose or some other piece of equipment, and they don’t have time to pull out their phone,” Sinclair told me.

Mojo’s interest in building AR contact lenses for first responders grew when it began talking with Motorola Solutions, the dominant provider of communications technology for that market. Mojo has been collaborating with Motorola to define a set of features that might bring crucial information to firefighters and other responders at just the right times. Motorola’s venture fund also invested in Mojo. Sinclair told me that Mojo is talking to the U.S. Department of Defense about some similar scenarios for the military, but didn’t go into details.

Mojo also wants to make lenses for people in service industries. Sinclair describes a use case where a hotel concierge can seamlessly identify and greet incoming guests based on data called up from a database and displayed within the lenses.

But the first version of the Mojo lens, which the company says will ship in two to three years, will most likely be a base model containing a core set of features for people with vision impairments. There are 285 million of them worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

These lenses could be used by people with various kinds of degeneration of the retina—the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye—and by people experiencing presbyopia, the normal loss of ability to focus the lens of the eye on small objects that comes with aging. The Mojo lenses, for example, can detect the text on a road sign in the distance and display it clearly. They can magnify objects or project them onto the part of the person’s retina that can still see well. The lenses can help people detect objects in front of them by increasing the contrast between the shades or colors of the objects. The lenses can also superimpose graphic lines over the hard-to-see edges of objects within the wearer’s view.

A timeline of Mojo’s progress so far, and what it plans to accomplish next. [Image: courtesy of Mojo]

For some people, this could be life-changing. “We can give them the essential tools they need for mobility,” says Ashley Tuan, Mojo’s VP of medical devices and one of four optometrists working at the company. “They just want to feel that they are normal. They don’t want people to feel pity for them or take advantage of them.”

Sinclair told me every pair of Mojo lenses will offer vision-enhancement features, with sets of custom AR features added on to serve the needs of specific vertical markets.

When I first met with Mojo a year ago, it was still very focused on developing the technology in the lenses, and its plans for matching that product with specific markets seemed somewhat fluid. Since then, the company has become more focused on developing the vision assistance features, for good reason: It says that when it presented the lenses to the Food and Drug Administration, it got a warm reception. Because the FDA was excited about the product’s potential for helping the visually impaired, it admitted Mojo into its Breakthrough Devices Program, which offers a development roadmap designed to get the lenses approved as a medical device.

As of now, Mojo still has a long way to go in its process of getting that certification. It’s already begun some of the studies it’ll need to prove the lenses’ safety and effectiveness, but it still needs to test them in real clinical trials. Sinclair says that those tests won’t begin for another couple of years. When I visited the company’s offices in early December, the company had only recently been granted its Institutional Review Board certification, allowing its employees to test the Mojo lenses with their own eyes—so it wasn’t a shocker that it wasn’t ready to let me try them for myself.

LENSES FOR CONSUMERS, EVENTUALLY

Only after Mojo has begun marketing its vision assistance and vertical market lenses does it plan on making lenses for regular consumers. Like the other versions of the lenses, the consumer incarnation will put helpful digital information within the wearer’s view to help them get things done. But the information will be more about life than work. For example, if you’re leaving the airport—perhaps with your hands full of luggage—the lenses might display arrows pointing the way to your car in the parking lot. They might put a pointer over your Uber ride as it arrives, and display the license plate number and other information. If someone rings your doorbell at home, the lenses might display a video of the person standing on the porch.

Whatever the primary purpose for wearing Mojo’s lenses, optometrists will play a key role as a distributor and gatekeeper. They’ll need to measure a would-be wearer’s visual acuity and the shape of their eyeballs, then send the information to Mojo, which will create custom lenses.

"IT HAS TO MAINTAIN YOUR PRIVACY, IT NEEDS TO BE SAFE, AND IT NEEDS TO BE TRUSTWORTHY.”

An optometrist’s involvement also helps engender trust in Mojo and the safety of its product, which will be crucial. Mojo, after all, will be asking people to put a technology-laden piece of plastic directly against their eyeballs. An FDA stamp of approval should also go a long way toward that same end.

Users will not only be asked to trust Mojo with their eyeballs, but with their data. People will soon realize the lenses potential for collecting information about all the things their eyes rest on, including products, places, political ads, and people. It’ll be on Mojo to assure them that the lenses don’t record that data and share it with advertisers or governments. Sinclair says the only thing the lenses will remember will be human faces they may have to recognize again, but even that data will be stored only for a short time.

Perhaps more problematic is that it’s not just the wearer that needs to be convinced about the privacy of the technology. People with whom the wearer comes in contact may be concerned that they’re being recorded. That was an issue with Google Glass—which other folks could tell you were wearing—and could be even more nettlesome with a technology as invisible as contact lenses.

The public’s opinion on the reasonable expectation of privacy in the digital age is evolving, but Mojo will have a lot of educating and assuring to do when its product finally reaches consumers. Sinclair is keenly aware of this, especially with his background at privacy-obsessed Apple. In fact he was talking about privacy the first time I met him a year ago. “It has to maintain your privacy, it needs to be safe, and it needs to be trustworthy,” he emphasizes.

ENGINEERING HEROICS

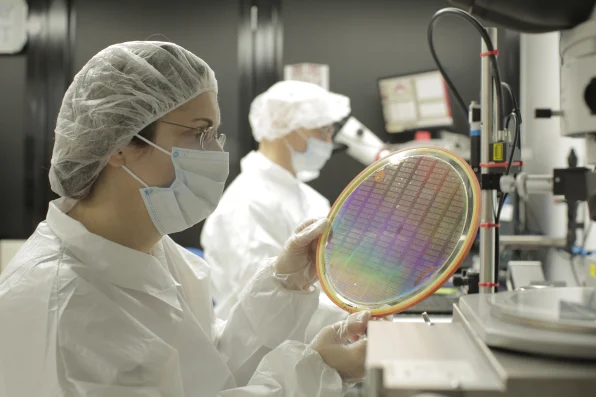

Mojo has spent the last three years turning Deering’s foundational work—his mathematical proofs and simulations—into a real physical product. And NEA’s Papadopoulos told me that it took a lot of long days and some real “engineering heroics” to overcome the technical barriers the Mojo people encountered along the way—barriers that could have stopped the development of the lenses cold.

Mojo clean room techs at work. [Photo: courtesy of Mojo]

According to Papadopoulos, early employees struggled to avoid thinking about all the reasons an AR contact lens was impossible and just get to work building it. He now believes that Mojo has emerged from that period and entered one where the road ahead is at least somewhat less treacherous. “It looks locked and loaded,” he says. “You know what you have to do, and there’s really nothing that seems scary.”

The main thrust of the engineering effort is now uniting, integrating, and orchestrating the various microcomponents. “We’ve tested pretty much everything outside the lens, and now it’s all getting pulled together in the lens,” says Sinclair.

Working with an incredibly tiny display requires some precision equipment. [Animation: courtesy of Mojo]

With the help of the FDA, Mojo’s lenses could become a visual assistance tool that helps a lot of people. But their future as a mainstream AR product may be less certain. Virtually every company building AR or mixed reality hardware is looking to the commercial market—rather than consumers—for early revenue streams. How many of those business customers will see contact lenses as a superior solution to AR glasses remains an unknown. And while consumer AR could end up being the next great personal computing interface after the smartphone, nobody really knows how it will play out.

All of which means that Mojo—for all the progress its creators have already made—remains a moonshot. “The fact that a lot of companies are still struggling to do all that in a headset, and that these guys are at least talking about doing it in a contact lens is super interesting,” says IDG analyst Tom Mainelli. “Color me skeptical, but we don’t make leaps without people taking chances like this.” For those who doubt that Mojo can turn its bold concept into reality, only seeing will be believing—once the company is ready to project the proof right onto their retinas.

SOURCE:Paper.li

Comments