SLACK CEO STEWART BUTTERFIELD ON COMPETING WITH MICROSOFT, THE FUTURE OF WORK

- The Tech Platform

- May 31, 2020

- 39 min read

SLACK CEO STEWART BUTTERFIELD ON COMPETING WITH MICROSOFT, THE FUTURE OF WORK, AND MANAGING ALL THOSE NOTIFICATIONS

t’sIt’s hard to remember what remote work was like before Slack. The company was founded in 2009, exploded in popularity in 2014, and has seen a new wave of growth during the COVID-19 crisis. Along the way, it’s reset expectations about what collaboration in software can look like, kicked off new conversations about being available at work all the time, and inspired Microsoft to launch an all-out assault with its competitive Teams software.

“Microsoft is perhaps unhealthily preoccupied with killing us,” says Slack CEO Stewart Butterfield.

Butterfield joined me on The Vergecast to talk about everything from racing to meet the surge of users during the pandemic, competing with Microsoft, the future of offices, and keeping Slack as an Electron app on the desktop.

And, of course, we talked about managing all of those messages.

Nilay Patel: In late March, you had a long tweetstorm about how Slack’s growth exploded as the virus started to hit, people started to say home. The number you had here was that you went from 10 million users to 12.5 million users in basically just a couple days or a week. Is that pace still going? Is it still crazy for you? Has it slowed down?

Stewart Butterfield: Yeah, definitely not on a percentage basis because we would have taken over the world.

But yeah, we were talking there about simultaneously active users. So Slack is very intensively used up to a couple hours a day for paid users. And that’s one of the interesting ways to measure the impact is to think about how many billions of hours — it’s just a couple of billions at this point — that people spend on Slack, which is a great responsibility. Hopefully, they’re doing mostly productive work, and hopefully, in an investment that pays off.

But this has been a particularly crazy time for us, as it has for everyone. But in addition to the “Holy smokes, we all have to work from home. What are we going to do? How are we going to manage this?” there’s been the business results. I am a little limited in what I can say about the specifics, just because we’re in the quiet period leading up to our earnings next month.

Did you have to make any changes on the back end in terms of meeting all that demand? Were you able to scale? Maybe this is overstating it, but Slack is a critical part of our workday at The Verge. It’s a core piece of our infrastructure. I know lots of other people feel that way as well. How did you make sure you could survive the onslaught?

Yeah, there’s a couple different angles. So on the purely technical infrastructure side, we actually had made, fortunately, a number of investments over the last year and a half, but especially the last six months, which automated a lot of the scaling. So as demand increases, capacity increases largely automatically. So that was great.

But we did have to scale a bunch of things. One, we asked all of our salespeople to reach out to each of their customers and ask if there’s any way we could help. That was in the first 24 hours. So that’s creating a lot of communication back and forth. And we also offer free 20-minute one-on-one consults, either on how to use Slack or remote work tips or any of that stuff, so we had volunteers across the company to try to keep up with demand.

“IN EVERY RESPECT, IT WAS A SCRAMBLE.”

But in addition to the demands on the technical infrastructure, there were demands on our support infrastructure, the customer success managers. But also, everyone’s just super busy. Our existing customers expanded their usage. At the individual user level, people expanded their usage. And there were brand-new customers and brand-new people evaluating Slack. So just in every respect, it was a scramble.

The good news was, there’s a lot of adrenaline in the first couple of weeks, and also a sense of purpose because it felt important that we allow you and all the other newsrooms in the country to continue to operate, and the scientific researchers on Slack, and the health care providers, and the disaster response people. I think everyone likes to see their work have impact. And at that time, there’s a real feeling like, “We are made for this.”

One of the first things I said to our team [when we went all-remote] was, “Hey, it’s great to do [everything] in chat, [but] you actually need to pick up the phone a bunch because you can be more mean in chat than you would ever be in person, just by accident.” Are those the kinds of tips you are giving to large organizations? Or was it more practical, like, “Here’s how to name all your Slack channels?”

It’s actually the whole thing. For a lot of people, it’s a totally novel and unfamiliar way to communicate, so just the concept that there are channels and other people can see this — who can see exactly? I don’t know if I want to have this conversation in front of my boss or random colleagues across the company.

So it’s everything from the sociology, the etiquette, or what linguists call the pragmatics of it, to literally how to operate the system and set policies.

There’s so much of using Slack that’s, like, telling people to not at-here everybody in a channel, and then there’s so much of using Slack that’s somehow mating your corporate process to a chat app and an interface in a channel design. Are you in the weeds as people move to remote work and deploy software like Slack?

Yeah! And there’s some things that seem like they’re very trivial but end up being important. My favorite example is, because we used IRC, we were used to receiving notifications only when someone mentioned our name or sent us a message directly, so that’s how Slack works.

Most people are coming from messaging systems where you get a notification for every message because, obviously, the volume is much lower. So if you’re on WhatsApp or Instagram DMs or whatever, you get a notification every time anyone sends a message, which would be crazy in Slack. So it turns out that mentioning people’s names is really important [in Slack]. And everyone understands the mechanics of [at-mentioning names] because Facebook has 1.5 billion users or more. And if you at-mention someone on Facebook, they get notifications.

But there’s not necessarily a feeling that you can trust your colleagues’ discipline about remembering to mention you when something requires your attention at every organization. Whereas at Slack — Slack, the company — we kind of grew up that way. If I get back after a bunch of meetings or something, and I see 100 unread channels in Slack, but only three of them have the red notification bubbles, I’ll just check those three, and then go back to what I was doing. The other 97 I could check at my leisure or when I have a question or when I want to catch up on something.

If you don’t implicitly trust that people will mention your name anytime something requires your attention, and you see all 100 of those channels as things you had better check because maybe there’s something important for you, then, suddenly, the whole thing seems overwhelming and unworkable.

So the training of stuff that seems trivial and insignificant can end up being really important to the actual dynamic. But the basic thrust for everyone is: create a channel for everything that’s going on across the company, every conversation, every project, every initiative, every team, business unit, office location, literally everything. And once you do that, everyone knows where to go to ask their question, everyone knows where to go to get their update, everyone knows where to go to get caught up on something. And that’s really transformative.

I think the bigger the company, the more significant it is.

I have a lot of questions about how you think about managing Slack channels. But connected to this is the idea that user interfaces will drive people’s behavior and then obviously be in a feedback loop with that behavior, and you’ll capture it. And well, during all this, you rolled out major redesigns of your apps.

Did you think, “Oh, we should hit pause and not roll out these redesigns because everyone’s coming to this interface and we’re about to change it on them”?

Yeah. Unfortunately, there’s just never a good time. And I am also a user of software, and over the last 25 years of making software, I think I’ve gotten good at training myself to look at Slack the same way I look at the Comcast xFi management thing...

I hope you look at Slack with a little more affection!

Well, yeah. There’s affection. But the point is, everyone finds it easy to criticize other people’s stuff. If you needed to change your 401k, it’s like, “Oh my god, these guys are a bunch of idiots.” Or you know, something with Verizon or your bank or applying for a Visa.

“IF YOU WORK ON THE PRODUCT TEAM AT SLACK, YOU KNOW ALL OF MY OPINIONS.”

It’s tough to do that to your own stuff. But again, I think I’m pretty good at it. I have many frustrations. If you work on the product team at Slack, you know all of my opinions. At the same time, even if something is definitely better than the current design, it can be tough for people to switch, just because they get so used to something, and it’s not about whether this is a better design, in some abstract sense. It’s “I have muscle memory to do it this way, and now you’re asking me to do it that way, and that’s disruptive to me because I don’t really care about Slack or what the UI is like for other people.” But yeah, we can’t stop changing it.

Did you ever have the moment where you were like, “We actually need to hit pause on this,” or were you full speed ahead?

Full speed ahead. I mean, there’s a little bit of pausing because, at the really high end, for large customers, we don’t provide them support for their internal IT system, and that’s the way that they want it. So they often ask us to hold back on changes for their company until they have more time to plan for it. But for the general audience, no, because we haven’t been ready for a while.

Slack, as a company, obviously, you make the software. You enable people to work remotely. [But you also] have an office, people work there. Are you thinking differently now about how you might organize your company in terms of where people work?

Oh, absolutely. So, no conclusions. My style is: if I have to make a decision now, I would like to make a decision quickly and clearly. If I don’t have to make a decision now, I’ll wait. Because I like the optionality.

And at this point, we just have no idea. And it’s not a decision that’s entirely up to us — Slack, the company — because we exist in a marketplace. And you can imagine if every company with whom we compete for talent decided “20 or 30 or 40 percent of our employees will work from home full time, and for everyone else, there’s this flexibility. So maybe you come into the office a couple times a week, or maybe you work from home for a week, and then come into the office every third week,” and we don’t do that. Then, first of all, they’ll just have a bigger pool of talent to choose from. And also, Slack employees who over this period, realized, “Damn, I want to actually live closer to the rest of my family back east,” or whatever it is. “I want to live somewhere where I can see a lake.” Those people would leave and go somewhere else.

“OFFICES EXIST PRINCIPALLY TO FACILITATE PEOPLE SITTING AT DESKS USING COMPUTERS.”

So there’s a degree to which we’ve got to stay in line with the market, but I’m also excited about, personally, reimagining what that physical space is for. Because we spend an extraordinary amount of money, and those offices exist principally to facilitate people sitting at desks using computers. Whereas they could exist principally to allow for more effective collaboration, which means a bigger variety of spaces more dedicated toward meetings, a smaller number of fixed desks, and the expectation that if you already have this giant list of work, and you just have to plow through it, then stay home. And when it’s time to do the roadmapping session to get together with the team and think about what you want to do next, then come to the office.

And then once you have your work cut out for you, you can go back home.

I think about that a lot, particularly as it relates to Slack because Slack obviously disintermediates you from a physical location in a very effective way. But it also means your work can come with you all of the time. That’s maybe the main complaint I hear about Slack: it’s chasing me around. And so we are always telling people to turn off their notifications. Is that part of your training as you roll it out to big organizations, to be responsible in how you use it?

Yeah, absolutely.

And again, Slack the company uses Slack the product in a super-specific way. And we evolved from eight people to 2,100 or however big we are now, using Slack the whole way. So we view it as kind of as synchronous as you want it to be. So it can be completely asynchronous, “I’ll get back to this in 36 hours from now,” or it can be immediate back-and-forth. There’s a lot of — never explicit rules that we taught people, but just habits that developed in the culture. Things like adding the eyeball emoji to a post just means “I’ll check this out.”

Someone, I don’t remember who now, called faves on Twitter, the “humane read receipt.” Like, “I took explicit action to let you know that I looked at your response.” So if you do that, then there’s usually less pressure to respond.

But this is something that happens over and over and over again. I remember reading a [Wall Street Journal] story in 2000 or 2001, that was like “BlackBerrys. They’re ruining our lives,” and it was illustrated with a woman pushing a shopping cart in a supermarket with two kids tugging on her arm, and in her other hand is her phone, and she’s answering messages. The complaint was, “We can’t get away from this stuff. It follows us on vacation. It’s in the evenings and first thing when you wake up.”

I think any time there’s a technological shift, it takes a while for, really, like almost low-level social physics — I don’t even want to say sociology — to figure out the right equilibrium point. Because if the culture is, “I’ll get back to you when I can or when it makes sense,” then, suddenly, there isn’t that expectation, and people don’t feel obliged to respond.

“WE ACTUALLY CREATED DO NOT DISTURB MODE, MORE FOR THE SENDER THAN THE RECIPIENT”

Let me just give you a quick illustration of how complicated it truly is. I want to send you something. It’s 11PM, I’m worried I’m going to forget. It just occurred to me to ask you this question. So I can send it to you at 11PM. But I’m the boss, and people will just assume, “Oh, he sent it to me now. I gotta get back to him.”

So we actually created a Do Not Disturb mode, more for the sender than the recipient, so the sender could feel comfortable sending it and not have to remember this thing because they knew that the recipient had the control to turn the notifications off. But we also know that people generally don’t change the defaults, so if we didn’t make it default on, then most people wouldn’t use Do Not Disturb. But we also knew that people had keyed workflows off of notifications, things like if you’re on call or on rotation for monitoring a network or something like that.

And also, we don’t know exactly how that company works, so we want the boss to be able to override whatever the preferences are. But also, probably, you should give individual users the power to override whatever the boss said.

So the way we ended up doing it was we set everyone in Slack to — I think it was 8PM to 8AM — notifications would be off in your local timezone, but we didn’t start it yet. And then we told all the bosses, “Here’s the default, you can change the default for your team,” and then we turned it on for everyone. And it’s worked, but it’s a very subtle problem, and that’s just about notifications.

I will acknowledge freely, because I’m almost an eager critic of Slack, that it would be much easier to treat it more asynchronously if it was easier to catch up. Most heavy users do what I do, which is mark tons of channels unread, or maybe you use the saved items feature, or you use reminders, however it is, you kind of develop your own way of coping with all the stuff you want to follow up on, and we don’t make that very easy.

We could make that trivially easy, and if it was as easy as it is in email, where you can definitely miss stuff and you can fall behind and get overwhelmed. But, you know, you look at your email inbox, and it’s essentially a to-do list, and you can easily delete and archive things. You can’t miss [something] really.

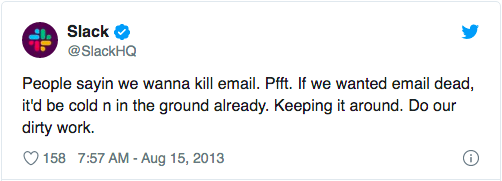

When Slack was beginning, when that first wave of explosive growth took off, I think we wrote this headline, everyone else wrote this headline: “Slack is going to kill email.” That has not happened, as near as I can tell. Is that still the goal? Was that a framing that you just took because it was powerful?

August 14th, 2013. This is a tweet from Slack. “People saying we want to kill email. If we wanted email dead, it’d be cold and in the ground already. Keeping it around, do our dirty work.”

We never said that we would eliminate email.

[Slack, the company, is] the extreme. We don’t use email for internal communication at all, ever. No one would ever email anyone else. And I think there’s tens of thousands of smaller companies that have evolved that way in their use of Slack over the years. But that’s not a change that’s going to happen in under five years, and probably more like a decade, for a lot of organizations. If people have been there 20 years and developed workflows around email, you can’t just stop.

“WE DON’T USE EMAIL FOR INTERNAL COMMUNICATION AT ALL, EVER.”

And there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with email. Think of the virtues of it: it’s an open standard, universal namespace, anyone can run an SMTP server. So it’s the lowest common denominator in a really positive way. And I think you want those advantages, but none of those are advantages when it’s just internal communication where you can select a specific platform.

Channel-based messaging platforms like Slack genuinely make life a lot easier because you join the team — you know, people started [working] at Slack yesterday. And there’s, I don’t even know, 15 million messages in the archive that are available for them to search. For their team that they work with most closely, they can scroll back over the last couple of weeks of conversations and see, not only the facts and projects that people are working on, but also how people relate to one another, what the sense of humor is, and all that stuff.

I think the net of that is you get up to speed two times faster or three times faster — I’m just making up the number, but so much faster. And the same thing is true for changing teams inside, getting up to speed on something. Because the advantages are so significant, I think that shift is inevitable. And of course, bringing it back to the current situation, I think a lot of organizations just got shoved down that timeline of inevitability by 6, 12, 18 months or, in some cases, probably a couple years.

We use Slack for everything, and yet, when we want to formally communicate something, it’s still an email. There’s some sort of letter-writing formality to email. Or in the case of your 11PM [example], I won’t Slack it because I know that everyone has their notifications on because it’s a newsroom, and they’re maniacs. I will literally email it, and at the top of the email, say, “This can wait.” Because it’s fully asynchronous, and it has that formality to it. Are those things you want to bite for Slack, that way of communicating priority or communicating formality?

We implemented APIs for scheduled sending of messages, and I think we’re going to end up putting that in the product at some point. G Suite has it now. I don’t know that they’ve normalized it in the sense of most people use it, but at least there’s a billion-plus user bit of software that has that built-in now. So I think from that perspective, we’re much more likely to give more and more tools that allow you to keep track of the things you want to get back to. More control over notifications, scheduled sending all that kind of stuff.

“WE IMPLEMENTED APIS FOR SCHEDULED SENDING OF MESSAGES, AND I THINK WE’RE GOING TO END UP PUTTING THAT IN THE PRODUCT AT SOME POINT.”

As for stealing the last couple internal roles for email inside of a company like the announcement of an acquisition or a divestiture or an executive change or something like that — that’s okay. They can still use email for that.

You’ve used the word “where” a couple times when talking about Slack. And I think that idea of knowing where to go to ask the question, knowing where to go to get the update, knowing where to go to get caught up on something, is the heart of it. And that can be accountants closing the books for the quarter or doing an audit because there’s just like all this back-and-forth about “How can this be deferred revenue? Why doesn’t this thing show up as an expense now?” Or it can be a group of marketers negotiating the Q3 marketing budget and, in real time, making their case for more online ads versus print or something. It can be recruiters organizing a job fair, it can be network engineers diagnosing production incidents. Really anything, whatever the work is that that group does, That’s what happens in Slack. And all of that would be terribly served by email.

Slack, for many people, is also a social space. It is a personal space. Slack groups are forming for all kinds of things that have nothing to do with work or careers or professionalism. Are you thinking the product needs to shift to serve your business customers and the people who are using it to hang out with their friends?

“No” is the short answer. And not because I don’t care about it, but because it’s very, very hard to do both of those well. And I think that most of the kind of accommodations you would make for one side or the other actually make it worse.

“FOR A STAR WARS FAN CLUB, SLACK WOULD BE A TERRIBLE TOOL.”

While you were asking that question, I was thinking about my own personal use of Slack, and that’s down to just my family Slack, which is fiancée, work assistants... that’s about it. That’s for more like shopping lists and vacation ideas or maintenance that needs to happen on the house or something like that. Whereas all the little back-and-forth during the day, [is] in iMessage. So it’s not that we’d want to make it hard for people to use for personal reasons. The personal uses of Slack that most fit the shape of Slack are those where it’s still a group of people that are aligned around the accomplishment of some goal or set of goals. That could be planning a wedding, a home renovation project, or just operating their family. You know, between kids’ lessons and school and homework and travel and all that stuff.

That’s opposed to people who just have a natural affinity — like a Star Wars fan club, Slack would be a terrible tool. Something like Reddit would be much better, and thankfully, those things exist.

I mean, Discord exists. It is mostly communities around games — I guess games are a kind of project in one way.

But when Slack goes down, [The Verge team goes] to Discord. It’s a very different product, a different audience, but at the core of it, it’s channel-based messaging. So we can actually operate inside of Discord. Do you think of Discord as a direct competitor?

No. So I think you’re right, that, functionally, experienced users could temporarily substitute Discord for Slack. It depends. If you have any real use of the platform, then I think that you wouldn’t be able to carry that over. And there’s a couple of other things.

The entire Verge doesn’t go over. It’s the core newsroom operation. And it’s still pure chaos, don’t get me wrong. But we’re able to do it.

People have a hard time getting over associations. The first time a Slack employee asked me about Discord internally, like, “Shouldn’t we be worried? We see open-source projects moving over [to Discord],” I struggled to find the right analogy. But if Apple launched a vodka brand — Apple just doesn’t do anything for vodka. Maybe I would be more inclined to buy that vodka than something else. But it doesn’t translate its cachet in that way because people just form associations.

Slack is already a pretty messed-up name for a workplace productivity tool — Discord is significantly worse in that respect. But if you go to the website, and it’s all this stuff about gaming and live chat and stuff like that, and you’re coming as a VP of End User Productivity inside of 40,000-person financial services organization, and you have to be FINRA compliant and, for other regulatory reasons, it needs to be ISO 27001 and 27018 and blah, blah, blah, blah. Obviously, you’re not getting that at Discord.

“PEOPLE WHO THINK THEY COULD MAKE SLACK IN A WEEKEND ... I THINK 100 PERCENT OF THEM WOULD FAIL EVEN TO GET 10 PERCENT OF THE WAY THROUGH AUTHENTICATION.”

And I think it would be foolish for them to add all that stuff because it’s super complex, and, in the same way, for us to add a really great capable set of purely social tools would also be very complex. Good software is just very, very hard to make. And so, you know, there’s a lot of people who think it’s just X, where X is some app that I already know, and kind of dismiss the effort that goes into it.

People who think they could make Slack in a weekend or something like that, first of all, obviously, it’s just impossible. I think 100 percent of them would fail even to get 10 percent of the way through authentication in Slack, because you have to support different SSO providers and the SAML protocol and two-factor auth. That’s how I look at all other software. Like I don’t want to do what Salesforce does. I don’t want to do what ServiceNow does. I don’t want to do what Atlassian does. If we can get away with just doing what Slack does, and ideally being a multiplier on the value of all those other tools, then that’s a great position for us, and it’s a great position for customers as well.

You brought up Atlassian. They obviously operated HipChat — it’s gone. At one point, Basecamp had Campfire — Campfire is gone. Why do you think Slack won and beat out all those competitors? And now, there’s a handful of big competitors I want to talk about, but Slack has eaten that entire market. Is that a network-effect thing? Is that a user interface familiarity thing? How did that happen?

I think it’s hard to pull these apart. And I think in situations like this, there’s always an element of luck or timing, or one particularly influential person decided to use it.

People really rely on social proof. So if you hadn’t heard of Slack at all, and then, suddenly, out of the blue, someone tells you, “Everyone’s switching from product X to Slack,” and then, suddenly, you notice everyone’s saying that, you’d think, “Everyone must know something that I don’t know.” So there’s a gravitational force or increasing return dynamic once it starts.

But the reason that I think it took off relative to HipChat and Campfire and other tools at that time, is really a very basic feature. We kept what we call a cursor position, or what’s the most recent message you’ve read up to, in every single channel, and we immediately sync that across devices. So you could walk across the room, scrolling on your phone, sit down at your desktop, and you’re in exactly the same position. People forget that, until Slack came along, the other apps didn’t do that. So you always had — for every single channel — to go find the point that you had read to last, which is incredibly cognitively taxing and incredibly time-consuming.

It turns out that one feature was really critical. I don’t mean it was all about that — it was also a nicer-looking UI, deeper integrations, whatever. I’m sure there’s many other features besides that one. But I really feel like that one was such a profound difference in the experience of using the product.

It’s funny to see Microsoft go all out on Teams to try to take on Slack, which is a much smaller company. Do you think that they can steal some of your moves that were used in that early period to win? Is that a competition you see as directly as they appear to [see it]?

It’s complicated. I don’t think the same moves are available to them. Because I’ve never heard anyone say, “We’re going to use Teams instead of Slack because we think it’s a superior product.” I don’t mean that that’s never happened, but I’ve never heard it.

They also end up being quite different. There’s definitely a sense in which — well, this is how it feels on the inside of Slack — Microsoft is perhaps unhealthily preoccupied with killing us, and Teams is the vehicle to do that. But Teams is much more of a direct competitor to Zoom. If you watch their product announcements or read their press releases, if you look at the features listed, if you think about the 100 million people who are being migrated from Skype for Business to Teams — it’s voice and video calling. And Slack has some very limited voice and video capabilities built into it, but that’s definitely not why anyone chooses to use Slack.

“MICROSOFT IS PERHAPS UNHEALTHILY PREOCCUPIED WITH KILLING US.”

So in that sense, they’re not directly competing at all. The advantage that they have is [that] lots of enterprise customers already have Office 365, [and] Teams is just there for free. So rather than, “We did an evaluation, and we tried both Teams and Slack and fully examined all of the possibilities for how we might be better collaborators in this digital age,” it’s just, “Don’t turn it off because it’s already turned on for us by default.”

At the same time, Teams has been out for three-plus years, and almost our entire enterprise business has grown up in the face of Teams. Our revenue has doubled, and doubled. I think at some point, people, the narrative will shift. If it’s quarter after quarter of us delivering results that show growth in enterprise and just continued growth across the board, then the idea that Microsoft could just crush Slack will go away. Because if they could have, they definitely would have.

You think about this press release they put out in July of last year that had a chart of their daily active users and Slack’s daily active users with a Slack logo and Slack name on their press release — no software company has ever done that. Like, maybe at the height, Oracle would do something like that. Oracle definitely puts their competitors’ names and charts in their ads, kind of notoriously. But literally, no one else would ever do that. Microsoft has never done that before. And that’s at a time when we had 1/200th the revenue.

It kind of speaks to the commitment they have there, and it is uniquely Slack. So if you Google “Spataro Slack” — Jared Spataro is a [Microsoft] corporate vice president — you see a bunch of shit-talking about how Slack isn’t very good. But if you put in Spataro and Okta, another company with whom Microsoft competes with the free bundled product, no mention. If you put in Spataro and Google, no mention. If you put in Spataro and Amazon, no mention. So, it is really specific to Slack, and there’s a lot of background. But the point is, Microsoft benefits from the narrative that Teams is very competitive with Slack. Even though the reality is it’s principally a voice and video calling service.

“IF EMAIL BECOMES LESS IMPORTANT, THEN THAT WHOLE $35, $40 BILLION-A-YEAR COLLABORATION PRODUCTIVITY BUSINESS UNIT IS THREATENED.”

And the reason for that, I think, is if you imagine two years from now — imagine Zoom just cleans up, 98 percent share. Cisco says, “Forget it, we’re out, You know, we can’t compete with this.” It doesn’t really matter to Microsoft’s core business. Whereas, in a different universe where Slack is incredibly successful over the next two years and 98 percent of knowledge workers use Slack, it does matter to Microsoft because the relative importance of email is hugely diminished. And in a world where Windows doesn’t really make a difference — doesn’t give them any leverage to enterprise buyers, what gives them the leverage? It’s that people are used to Outlook, and we already set up Exchange. There’s a billion other things that are connected to it, and it’s really complicated to shift. But it’s really about email, and if email becomes less important, then that whole $35, $40 billion-a-year collaboration productivity business unit is threatened.

You’re saying that — Exchange Server, Active Directory, all that stuff — Slack’s growth and success actually ultimately represents a threat to that and then the bundled software products with it?

I don’t mean that you would use Slack instead of those things because, obviously, they need totally different stuff. I just mean that the leverage that comes with that core set.

If you’re serious about making slide presentations, then PowerPoint on Windows is way better than most other things. We’re a customer of Office 365 at Slack because there’s lots of finance people in the world who are like, “I can’t do this in anything but Excel, like it’s just flat impossible.”

But you wouldn’t buy, you know, $30 million worth of Office 365 for every single person in your company in a site license, unless you thought that email, Outlook, Exchange, and that kind of central calendar, Active Directory, all the kind of attendant stuff was especially important. And again, if email declines in relative importance, maybe there’s a lot of customers who say, “Okay, well we’ll use G Suite for the main stuff, and we’ll just buy some licenses for Excel for the people who need it.”

[At The Verge], we use Slack, we use Zoom, we use G Suite. We sort of cobbled together an office suite from multiple vendors. In this moment, Slack offers some video call functionality, but it doesn’t offer group video calls. It offers some audio calling functionality. Do you think that you need to grow that and become a competitor to Zoom? Do you think you need to partner with Zoom? How do you think about forming the colossus against the Microsoft colossus?

Here’s one thing I think people don’t really realize or haven’t fully internalized yet. I’m going ask you to imagine a bunch of graphs. The specifics don’t matter, but [imagine] the slope of these graphs: number of minutes that knowledge workers spend using software per day from 1970 until now. Number of different software tools or services used by an average knowledge worker from 1970 til now. Number of software companies that exist. Number of software companies with more than $10 million in revenue. Number of software companies with more than $100 billion in revenue. The average number of software services in use by a large enterprise.

Every single one of those is more or less on the same trajectory, and it’s not like it just stops this year. Those are multi-decade trends that will continue. The average large enterprise now has 1,000 different cloud services in use. Even us — we’re only like 2,100 people — but we buy from 450 different vendors, and that’s not different products. That’s different vendors. I don’t even know if I could name 450 different software companies, but, apparently, that’s how many just Slack buys from.

People forget all the stuff. You choose any simple-seeming business process, and there’ll be 10 or 15 tools behind it. You want to make a job offer to someone, you reflect that in Workday, and then you create an offer letter in your collaboration tool after scheduling the meetings with your recruiting scheduler specialty calendar software, and you send out the DocuSign, and store the copy in Box, and use ServiceNow to provision them with tools, and all that stuff.

So people are going to use more software. Our position has always been: for whatever software our customers already use or whichever they choose to use in the future, we’d like to make their experience of those tools better because they use Slack. So just to put that a different way, if you use Dropbox, we want to make Dropbox better for you because you use Slack. But the same thing is true if you use Box or G Drive or SharePoint, OneDrive — it doesn’t matter to us. We’d like to make your experience of those tools better because that’s the kind of space we can imagine makes the most sense for us. It’s horizontal.

If you think about different product categories as verticals, the traditional enterprise software business model has been to choose a vertical, make a product, get some customers, and then choose an adjacency, and then sell the new product to the old customers and just keep on doing that over and over again.

“TO THE EXTENT THAT THERE’S A SECOND ACT, IT’S ANOTHER HORIZONTAL.”

I don’t think that’s the way Slack is going to grow in the future. To the extent that there’s a second act, it’s another horizontal. Another thing that extends across those services because the one kind of negative consequence of the additional minutes, the dollars spent, the number of tools in use, is that the value of interoperability becomes greater.

The siloing and fragmentation of knowledge into these different systems, while it’s still definitely a huge net plus to use them, is a real challenge for organizations. And if you have this central medium, you have this lightweight fabric for systems integration. It’s disproportionately valuable. And I think that’s it.

I know that Microsoft’s total revenue from software is around 6 or 7 percent of all software revenue. And they’re the biggest, right? So behind them is SAP and Oracle, and I don’t know what percentage to have... 4 percent, 3 percent or something? That means that, you know, 90-plus percent of all revenue from software is from companies other than Microsoft, Oracle, and SAP. There’s just a huge, huge long tail, and that’s unidirectional. There’s going to be more companies, more dollars spent per employee per year. More minutes spent in software every year. That’s just an inevitability.

So when Google is like, “Oh my god, we blew it with Google Meet. We have to try harder to compete with Zoom.” That’s a thing we see happening right now. You don’t feel that pressure to expand the capability of Slack into a video in that way?

No, because I don’t — this is the challenge for us to be clear — but, 90 percent of the time we’re selling into a new category. So that can be tough because, if it’s a zero-based budgeting approach, no one has the budget for a new thing they didn’t buy last year, and you have to explain what the new thing is and why it’s valuable. On the other hand, you don’t have to compete directly with anyone.

Whereas, if we came in and said, “We’re Slack and also all the things that Zoom does,” and you already have Zoom, or Teams, or Cisco, or Meet, or whatever, now we have to convince you to change. I don’t think we’d get any additional revenue from that customer if they’re using Slack and the calling service. I don’t think it’s especially, necessarily, more attractive. In fact, a version of Slack that integrates very deeply with Zoom or Meet or Teams or Cisco — that’s attractive. We’re almost never going to have the best version in every dimension of that hypothetical calling service. So I don’t think it gets us any more customers. I don’t think it gets us any more revenue, and I don’t think it really is better for customers when compared to the alternative of deeper integration.

I’ve talked to other CEOs of smaller, midsized companies, and there’s always the looming threat of the giant, that we’re all going to end up working for three companies when this is all said and over. The consolidation is happening too much, the pace of new startup formation is too slow. That there’s all of this M&A activity and mergers, and Big Tech is getting bigger. It seems like you’re not feeling that pressure the same way? Just throughout this conversation, it doesn’t seem like that’s a thing on your mind.

No. I mean, it always seems like that in the moment. It would’ve been incomprehensible to anyone to suggest to anyone that the 1977 Albuquerque hippie version of Microsoft — I’m sure you’ve seen that photo where there’s 12 of them — that they would become more valuable than, at the time, what was the most valuable and powerful company in the world, IBM.

It would not make any sense to you that that was possible, and, looking forward, all you knew was, “Hey, it’s the year 2000, Microsoft owns Hotmail, has a big online presence with MSN, has 90 percent market share for operating systems, 90 percent market share for web browsers, basically complete control over the world’s population, how they get online, and now they’re going to compete in search with this 40-person company from Mountain View,” you’re like, “Of course Microsoft is going to win. They have a thousand times the resources, they have all of these smart people.”

They got in trouble for that.

Oh, I know. There are people inside Microsoft who believe this is only because of the antitrust — the Justice Department’s actions — but they sure lost there.

And same thing, you know, Google in 2007, saying “Damn, Facebook really is getting popular. Good thing we have the hundreds of millions of commenters on YouTube and the hundreds of millions of users of Gmail and the hundreds of millions of people doing web search because we will, for the first time in the history of the company, promote something on the homepage. We will force every YouTube account to use Google+. We will promote it inside of Gmail,” and they still got their butts kicked.

“THE SMALL, FOCUSED STARTUP THAT HAS REAL TRACTION WITH CUSTOMERS SOMETIMES HAS AN ADVANTAGE.”

There’s a million other examples, but the lesson of that is the small, focused startup that has real traction with customers sometimes has an advantage versus the large incumbent that has multiple lines of business. Partly for innovator’s dilemma reasons, partly because bigger organizations are slow, and partly just because, and this might be included in the other ones, there’s people in Microsoft who are better off in their career, or the prestige of their role, or their [compensation], or something, if Teams doesn’t win.

In other words, customers just buy Office365, so it’s zero-sum, internally, for recognition and acknowledgment with Outlook and Office365 Groups and with Yammer and with SharePoint.

Look, Facebook’s 17 years old, 16 years old? Whatever it is now, and the fifth-biggest company in the world, and there’s lots of companies in that category that are relatively new that are doing super well. I mean, we’re doing super well and we’re relatively new, and Zoom, same thing. So yeah, 10 years from now, it’ll be obvious, or 20 years from now, it’ll be obvious why those companies wouldn’t be dominating forever, and the new thing would come to take their place.

Do you think Microsoft is competing fairly, right now, against Slack? I mean, they are bundling the product, they are taking lots of shots at you. That’s a lot to be up against when you still have to charge licenses per seat.

I kind of got in trouble for this before, but I actually kind of like the term “unsportsmanlike” because I don’t know whether or not it’s illegal. That’s a question for somebody else.

I do know that [Microsoft is] not principally concerned with selling the product on the merits of the product, and the benefit it has for customers, but selling against something. And that seems unsportsmanlike. I don’t know about “unfair” in some absolute sense, like morally, judicially, but I also think, you know, it’s a tough thing to have work in the end.

Because here’s another way these things play out: Microsoft deploys Teams to company X, they get really used to it, and they find, “Wow, channel-based messaging is a way better way to get work done.” They build some integrations, and they start to get more and more of the company on it, and soon, the whole company is on it. And then they think, “Damn, it sucks that we can only have 5,000 people per instance, and it sucks you can only have 200 channels per instance, so there’s no way to federate them together. We should consider moving to Slack,” which allows organizations to scale to that level. Or “We’re kind of stymied by the platform capabilities, and we need much richer sets of integrations. We should move to Slack.”

So you can just get people used to the category and then, suddenly, it puts those customers in play down the line. So I think, at some point, you have to compete on the basis of: it’s a win for you as a customer to use this product.

That’s the way I look at us purchasing software. As a general rule — there are exceptions — all software we buy is a good deal, almost definitionally, because it should be replacing some part of someone’s job that could be replaced. You can only automate the automatable parts of people’s jobs, and those are usually not the parts that are demanding the use of people’s intelligence and creativity, so purchasing software frees them up to do something that’s a higher use of them. You have to sell software, ultimately, on that basis.

A while ago, you were talking about making it easier to use Slack. You were talking about having AI help to navigate the interface. That is in tension with “People are going to get used to our competitor’s product and then come to us.” If the interfaces diverge too much, you’ve got some problems there. Are you still thinking about radical changes to how the interface is navigated, to how AI might help you use it?

Yes. So kind of across the board, I think you can sequence things in such a way that it’s less disruptive to people. I think Teams and Slack are going to be quite disjointed, if you’re talking about switching, but Slack in 2014 looks pretty different than Slack in 2020. When you think about how it continues to change in the future, I think there’s opportunities for more AI and ML stuff, like our little-known people-search filter. So you type in a search query into Slack — you could be looking for a message or a document, like a specific one, or you could just be looking for information about this topic — and if it’s the latter, we suggest people who appear to be experts on that topic.

But then, I talked about the ability to kind of track and manage all the stuff you want to get back to in Slack. I think that’s a serious pain point, and just making people aware that there is a history stack that you can go back-and-forth through, that is often a huge relief. Teaching people some of the basics.

“I COULD ACTUALLY SEE A STORY-LIKE UI IN A CHANNEL FOR A GIVEN TEAM BEING PRETTY VALUABLE.”

But looking further afield, while I don’t think we’d ever build a calling service that has the same guts or purpose as Zoom, I think there’s opportunities for asynchronous video or audio communication. You see the obvious desire for this feature based on people’s use of WhatsApp and, to a lesser extent, iMessage. The tap to record, release to send a quick audio / video message.

When Facebook added stories right after Instagram, there was this joke about how all software would add stories. But I could actually see a story-like UI in a channel for a given team being pretty valuable. Because a lot of messages at the low level, for a group of people working together on something, are “I may be gone for lunch for the next 90 minutes because I have to pick my kid up on the way back,” something like that. But also, just a little update on how it’s going, how progress is on this project, and those could be effectively both delivered, created, and consumed in a way that might be preferable to text.

And then the last thing is, whereas we’ve learned to give individuals better control to track and manage all of the things going on in Slack, a collaborative means to organize the huge rush of information, to pull things out and curate them, would be a huge advantage. And for every single thing we could imagine doing ourselves, we would always try to make it available, at the absolute stub level, for any competitor product that people would want to plug in. Because if people could do that, it only kind of accrues to our benefit. The Slack with Slack-branded feature X is probably less valuable than Slack with competitor-branded feature X in the same slot.

I just come back to the notion that people use Slack both for work, and you’re very focused on work, but that is something you could apply to people’s personal lives as they use it as consumers in other places. Does that cross your mind? If you’re going to plan a wedding in Slack, could Slack just learn more about your wedding and suggest wedding vendors to you? Is that just too far afield?

It’s a totally different business, selling ads, and stuff like that.

I always use this story internally, because I’ve always liked it. But one of Aesop’s Fables is the dog with the bone in its mouth, and it comes to a pond, and it sees another dog with a bone in its mouth, which, in truth, is actually its own reflection. It opens its mouth to grab the other bone, and, as a result, drops its own bone into the water.

I remember a woman I worked with in 1998 or something like that had this incredible shoe collection Excel sheet. There’s lots of people who put their baseball cards into Excel. Excel for literally anything. In Japan, apparently, it was really big to use Excel to lay out business correspondence because, ultimately, you get this like super fine-grained table, and you can get anything to align with anything however you want. But if I’m in charge of Excel, do I say, “Let’s go after these baseball card collectors and shoe collectors and all the other myriad uses of Excel,” or are we going to stay focused on the thing it’s supposed to do well?”

At some point, all software turns into Excel or creeps into Excel. When you say you want to go horizontal again, do you want to build another office suite? Is that the goal for Slack?

No, because I don’t think the office suite will be as important in the future. I don’t mean that as a criticism of any company or any tool or anything like that. I just mean, think about the relative importance of files in your digital life in the workplace, to records in databases or objects in the cloud.

Twenty years ago, everyone had a shared M: drive or Z: drive or whatever at their office, and everyone had Windows Domain Controller, and we’re passing files back and forth all the time. And pretty much the only artifact of collaboration, outside of a handful of databases, were files. And now, for most people, most of the time, files aren’t very important. So if you’re in customer support, it’s the ticketing system. If you’re in IT, inside the company, you have IT asset tracking software and another ticketing system. I could go down this list forever, but files become a forever-decreasing category of relative importance, and those office tools are geared toward the creation of those files.

“I DON’T THINK THE OFFICE SUITE WILL BE AS IMPORTANT IN THE FUTURE.”

Now, they’ve all moved to the cloud, and I think that actually makes a tremendous difference. But the next difference is, someone will eventually crack the nut — Kota, Quip, Dropbox Paper — whatever it is that’s holding back this kind of glorious future where I don’t have to decide in advance whether this is a spreadsheet or a presentation or a Word document. I have all of those tools available to me.

Most things we end up creating at Slack, they want to be a complex object that contains a bunch of other things inside it. It has the presentation, but also, you can dig into the original stats. The chart isn’t always going to be a pasted screenshot of the thing that you made in Excel. I don’t mean to have a specific prediction or special knowledge; it is a little bit of a skate to where the puck is going, not where it is now. I think by the time we were able to build a useful office suite, it would be 2025, and the world would have changed already.

I’d be doing my team a great disservice if I didn’t do a lightning round, which is just feature requests for Slack.

Why can’t I automatically turn off pings on weekends?

There is no good reason. And that is on somebody’s list.

More granular options about what to send to mobile.

Not being worked on presently, an area that we’re definitely going to work on.

Why is this thing still an Electron app on desktop? My battery is dying.

That shouldn’t be happening as much anymore after the big Sonic release. [Ed note: Sonic was the code name for the latest version of Slack.] I doubt it will be native in the next two years, but never say never.

We talk about this on our show all the time. Is Electron, the prevalence of Electron, are you committed to it? If you ask the operating system vendors, it’s the bane of their existence. Is it just the bet you made, and you’re stuck with it?

It’s just very useful to take a fully developed web app and then make a bunch of changes. It’s not just the same app that you get in your browser. There’s actually a bunch of features that Electron allows us — to get out in the file system and the operating system more broadly. But it is a complex app. We have two native ones: iOS and Android. And it is much slower to develop in those environments than it is as a desktop app.

The places where it really shows up as a pain point for me, and this is not lightning round anymore, is offline mode. That’s the thing that I personally want the most because I spent so much time in lousy Wi-Fi environments. Though, who knows, maybe I never will again. Maybe I’ll never leave my house. I finally have a good network setup. But that used to be a problem for me. I travel all the time and have trouble connecting.

Okay, one more lightning round question, and it’s not really a feature request. Why is Slack still the same experience if your company is five people or 5,000?

It’s a good question. It’s not entirely — if there’s 5,000, you’re probably going to be using the enterprise grid product, which allows you to have multiple workspaces. But yes, it’s really challenging to find ways of organizing information that work for both.

There’s some automatic customization that we do now and some more that we are planning, but I think a lot of it is going to be either administrator-level or user-level customization to suit the specific needs of that person. If there’s only four people in your Slack, you don’t really need a whole bunch of predictive analytics about which Bill or which Mary you’re trying to autocomplete when you use the at-name autocomplete, whereas large companies, I think it becomes really important.

I end every CEO interview the same way: I always ask people how they spend their time. When do you work? Because I find it very challenging to sit down and do work as opposed to go to meetings. You’re a very interesting person to ask that question, given the nature of your business. [And] now you’re managing your company remotely. So when do you work?

It’s very different now, because by six o’clock, I don’t think I have the capacity to do anything else useful or interesting. Maybe a little bit, you know, 8:30 or 9PM. But generally, I haven’t been during this time. And I think that’s because so much more is getting done.

But then it depends on what you mean by “work.” So a lot of work is what I’m doing right now: being in meetings, talking to investors, talking to customers. If it’s like really deep thought about something, that’s almost always the weekend, while exercising or going for a walk or having a shower — all of the classic, “I’m not sitting at a desk” kind of tropes. That’s where the really more insightful stuff happens.

I think of working in this context as not communicating [in a meeting]. “I’m going to write the email. I’m going to read the article. I’m going to think about this. I’m going to generate some work product.”

I’m the CEO. So the job is pretty much 100 percent communication. I mean, for any manager, that’s most of it. It depends on how expansive of a view of communication you have. If it’s preparing or sitting through someone else’s PowerPoint, if it’s reading and writing emails, if it’s phone calls and one-on-one meetings and quarterly business reviews and roadmapping sessions and all that. Yeah, that’s pretty much the whole job.

Many of your answers have been very different. This one, to me, is striking in how different it is. Because I need to block out hours to just think about stuff before I can go communicate effectively, and it sounds like you just communicate all the time.

Yeah. I have to block out hours, too, in the least-effective way possible, kind of ADHD my way through 75 Chrome tabs and start composing an email. But I figure, “Okay, I’ve already composed this so it’s going to show up in draft, so I don’t have to worry about finishing right now. I can go back to the other thing that I just remembered I was supposed to do.”

I can’t really think until the volume on stuff goes down enough. I feel like most of the time, 80 or 90 percent of my cognitive capacity is used up with little loops that are spinning. And it might be every five minutes, every 10 minutes, every couple of hours, a couple days, but it’s, “Oh, shit! Remember to get back to so and so,” and I have to slay a bunch of those to have enough actual mental capacity to think of something new and original.

I will end on this: what is your relationship to Slack the software like, as a workplace productivity tool? How do you manage it?

I manage it quite effectively because…

That’s a perfect answer to this.

I know how everything works, so I can work around anything. So when something doesn’t work as expected, I know the way around it, and I’ve just built little techniques. I can find it overwhelming, not because there’s too many notifications coming in, but just because I have too much to catch up on. There’s too many things that people will ask me questions about directly, which I don’t think is the experience of most employees at Slack.

But otherwise, we have very good discipline about where conversations happen and when to send messages and how much thought to put into something. If you’re gonna ask 100 people to read your paragraph of text — take a moment to think through it.

If this is what we’re going to end on, I think it’s a really interesting thought for everyone: how much does your company invest in internal communication, in training people to be more effective communicators? Probably zero. And then people spend 100 percent of their time doing it, which is totally nuts.

We don’t do as much of it as I think we should, but we do a Slack 101 and a Slack 102 course for new employees coming in, and we also are a little bit more intentional about the culture of communication. Almost every company, people don’t do any training at all, and then they have their people spend all their time doing this thing for which they’re not necessarily well-equipped. So I’ll leave it there.

I like the idea that you have a perfect relationship with Slack because you know how it works. And also, because you can change it if you wanted to. That must feel great.

Oh, you have no idea.

Source: paper.li

Comments