Program hardware from the Linux command line

- The Tech Platform

- Sep 28, 2020

- 5 min read

Programming hardware has become more common thanks to the rise of the Internet of Things (IoT). RT-Thread lets you contact devices from the Linux command line with FinSH.

RT-Thread is an open source real-time operating system used for programming Internet of Things (IoT) devices. FinSH is RT-Thread's command-line component, and it provides a set of operation interfaces enabling users to contact a device from the command line. It's mainly used to debug or view system information.

Usually, development debugging is displayed using hardware debuggers and printf logs. In some cases, however, these two methods are not very useful because it's abstracted from what's running, and they can be difficult to parse. RT-Thread is a multi-thread system, though, which is helpful when you want to know the state of a running thread, or the current state of a manual control system. Because it's multi-threaded, you're able to have an interactive shell, so you can enter commands, call a function directly on the device to get the information you need, or control the program's behavior. This may seem ordinary to you if you're only used to modern operating systems such as Linux or BSD, but for hardware hackers this is a profound luxury, and a far cry from wiring serial cables directly onto boards to get glimpses of errors.

FinSH has two modes:

A C-language interpreter mode, known as c-style

A traditional command-line mode, known as msh (module shell)

In the C-language interpretation mode, FinSH can parse expressions that execute most of the C language and access functions and global variables on the system using function calls. It can also create variables from the command line.

In msh mode, FinSH operates similarly to traditional shells such as Bash.

The GNU command standard

When we were developing FinSH, we learned that before you can write a command-line application, you need to become familiar with GNU command-line standards. This framework of standard practices helps bring familiarity to an interface, which helps developers feel comfortable and productive when using it.

A complete GNU command consists of four main parts:

Command name (executable): The name of the command line program

Sub-command: The sub-function name of the command program

Options: Configuration options for the sub-command function

Arguments: The corresponding arguments for the configuration options of the sub-command function

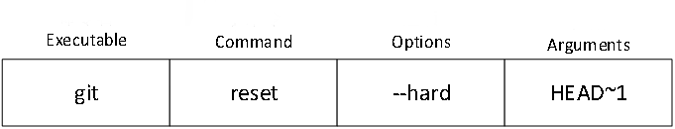

You can see this in action with any command. Taking Git as an example:

git reset --hard HEAD~1Which breaks down as:

The executable command is git, the sub-command is reset, the option used is --head, and the argument is HEAD~1.

Another example:

systemctl enable --now firewalldThe executable command is systemctl, the sub-command is enable, the option is --now, and the argument is firewalld.

Imagine you want to write a command-line program that complies with the GNU standards using RT-Thread. FinSH has everything you need, and will run your code as expected. Better still, you can rely on this compliance so you can confidently port your favorite Linux programs.

Write an elegant command-line program

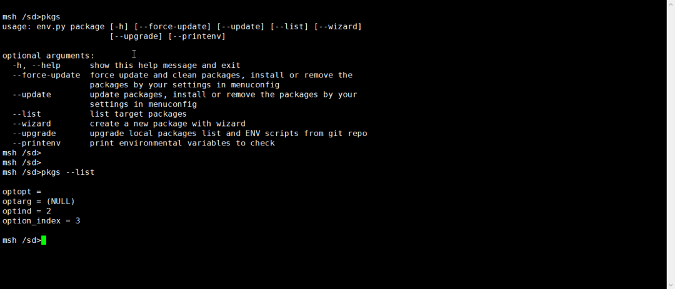

Here's an example of RT-Thread running a command that RT-Thread developers use every day.

usage: env.py package [-h] [--force-update] [--update] [--list] [--wizard]

[--upgrade] [--printenv]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--force-update force update and clean packages, install or remove the

packages by your settings in menuconfig

--update update packages, install or remove the packages by your

settings in menuconfig

--list list target packages

--wizard create a new package with wizard

--upgrade upgrade local packages list and ENV scripts from git repo

--printenv print environmental variables to checkAs you can tell, it looks familiar and acts like most POSIX applications that you might already run on Linux or BSD. Help is provided when incorrect or insufficient syntax is used, both long and short options are supported, and the general user interface is familiar to anyone who's used a Unix terminal.

Kinds of options

There are many different kinds of options, and they can be divided into two main categories by length:

Short options: Consist of one hyphen plus a single letter, e.g., the -h option in pkgs -h

Long options: Consist of two hyphens plus words or letters, e.g., the --target option in scons- --target-mdk5

You can divide these options into three categories, determined by whether they have arguments:

No arguments: The option cannot be followed by arguments

Arguments must be included: The option must be followed by arguments

Arguments optional: Arguments after the option are allowed but not required

As you'd expect from most Linux commands, FinSH option parsing is pretty flexible. It can distinguish an option from an argument based on a space or equal sign as delimiter, or just by extracting the option itself and assuming that whatever follows is the argument (in other words, no delimiter at all):

wavplay -v 50

wavplay -v50

wavplay --vol=50

Using optparse

If you've ever written a command-line application, you may know there's generally a library or module for your language of choice called optparse. It's provided to programmers so that options (such as -v or --verbose) entered as part of a command can be parsed in relation to the rest of the command. It's what helps your code know an option from a sub-command or argument.

When writing a command for FinSH, the optparse package expects this format:

MSH_CMD_EXPORT_ALIAS(pkgs, pkgs, this is test cmd.);You can implement options using the long or short form, or both. For example:

static struct optparse_long long_opts[] =

{

{"help" , 'h', OPTPARSE_NONE}, // Long command: help, corresponding to short command h, without arguments.

{"force-update", 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE}, // Long comman: force-update, without arguments

{"update" , 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE},

{"list" , 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE},

{"wizard" , 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE},

{"upgrade" , 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE},

{"printenv" , 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE},

{ NULL , 0 , OPTPARSE_NONE}

};After the options are created, write the command and instructions for each option and its arguments:

static void usage(void)

{

rt_kprintf("usage: env.py package [-h] [--force-update] [--update] [--list] [--wizard]\n");

rt_kprintf(" [--upgrade] [--printenv]\n\n");

rt_kprintf("optional arguments:\n");

rt_kprintf(" -h, --help show this help message and exit\n");

rt_kprintf(" --force-update force update and clean packages, install or remove the\n");

rt_kprintf(" packages by your settings in menuconfig\n");

rt_kprintf(" --update update packages, install or remove the packages by your\n");

rt_kprintf(" settings in menuconfig\n");

rt_kprintf(" --list list target packages\n");

rt_kprintf(" --wizard create a new package with wizard\n");

rt_kprintf(" --upgrade upgrade local packages list and ENV scripts from git repo\n");

rt_kprintf(" --printenv print environmental variables to check\n");

}The next step is parsing. While you can't implement its functions yet, the framework of the parsed code is the same:

int pkgs(int argc, char **argv)

{

int ch;

int option_index;

struct optparse options;

if(argc == 1)

{

usage();

return RT_EOK;

}

optparse_init(&options, argv);

while((ch = optparse_long(&options, long_opts, &option_index)) != -1)

{

ch = ch;

rt_kprintf("\n");

rt_kprintf("optopt = %c\n", options.optopt);

rt_kprintf("optarg = %s\n", options.optarg);

rt_kprintf("optind = %d\n", options.optind);

rt_kprintf("option_index = %d\n", option_index);

}

rt_kprintf("\n");

return RT_EOK;

}Here is the function head file:

Then, compile and download onto a device.

Hardware hacking

Programming hardware can seem intimidating, but with IoT it's becoming more and more common. Not everything can or should be run on a Raspberry Pi, but with RT-Thread you can maintain a familiar Linux feel, thanks to FinSH.

Source: Opensource.com

Comments