No, the Jobs Report Wasn’t Rigged. Here’s What Happened.

- The Tech Platform

- Jun 9, 2020

- 5 min read

The pandemic has complicated the usual methods and models for compiling employment data. But uncertainty has been offset by transparency.

When the Labor Department reported on Friday that employers had added jobs in May and that the unemployment rate had unexpectedly fallen, economists were surprised.

Others had a different reaction: suspicion.

Social media sites over the weekend lit up with posts, some from Democratic politicians, saying the jobs numbers were misleading at best and possibly manipulated. “The trump folks fudged the figures,” Howard Dean, the former Vermont governor and Democratic national chairman, said on Twitter.

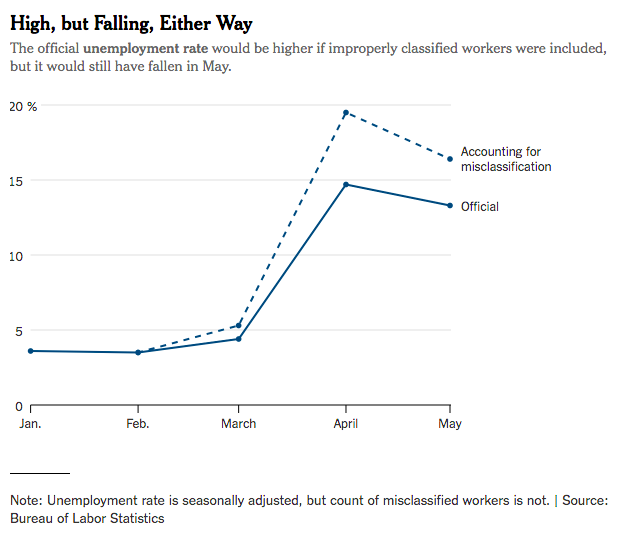

For many, those suspicions seemed confirmed by a note, deep within the report, saying some workers had been improperly counted as employed rather than unemployed. If those workers had been classified correctly, the unemployment rate would have been about 16.4 percent in May, rather than the official rate of 13.3 percent (although it still would have been lower than in April).

But economists across the political spectrum say it would be all but impossible to manipulate the jobs numbers undetected. And while there is no question that the speed and severity of the economic collapse has made gathering and interpreting economic data unusually difficult, they say the Bureau of Labor Statistics — the Labor Department office that produces the jobs report — has done an admirable job both ensuring that the numbers are reliable and publicly identifying potential issues.

“The B.L.S. acted with enormous integrity and transparency,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard economist who led the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama. “If anything, it’s another example of how honest and by the book they are.”

Moreover, Mr. Furman said, the essence of Friday’s jobs report is the same regardless of the classification issue: The unemployment rate fell somewhat in May from the previous month, but remains higher than at any other point since the Great Depression.

Here are some of the basics behind the numbers.

Why is there ambiguity about the unemployment rate?

In its report on Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics identified what it called a “misclassification error,” in which some people were mistakenly characterized as employed rather than unemployed. The same issue showed up in data from March and April.

To understand what happened, it helps to know a bit about how the jobs figures are calculated.

The unemployment rate and related statistics are based on a monthly survey of about 60,000 households. Interviewers, who work for the Census Bureau, ask respondents a series of questions about their activity the previous week to figure out whether they should count as employed, unemployed or out of the labor force entirely.

When the coronavirus pandemic began, the Bureau of Labor Statistics decided that anyone who wasn’t working because of virus-related business closings should count as unemployed, with or without a formal layoff notice. But starting in March, the agency noticed that an unusual number of people were being counted as “employed but absent from work” — a category meant to reflect vacation, family leave or other temporary absences. The bureau estimates that this issue probably affected about five million people in May. If all the potentially misclassified people had been counted as unemployed, the jobless rate would have been about a point higher in March, five points higher in April and three points higher in May.

It’s worth noting that the May report’s other surprising number — a gain of 2.5 million jobs — was based on a separate survey of businesses, and was therefore unaffected by the classification issue.

Why hasn’t the problem been fixed?

It isn’t clear why people are still being misclassified three months into the pandemic. The bureau says it and the Census Bureau are “investigating why this misclassification error continues to occur and are taking additional steps to address the issue.”

But Erica Groshen, a Cornell University economist who ran the Bureau of Labor Statistics under Mr. Obama, said it was not surprising that a survey intended to measure the ordinary fluctuations in the job market might struggle to capture the nuances of a pandemic-driven shutdown of a vast portion of the economy.

And once the survey has been completed, the agency is extremely reluctant to make any changes, Ms. Groshen said — in part because doing so would invite charges that the agency was massaging the numbers for political or other reasons.

“That would open up a Pandora’s box of ‘Why don’t you adjust for this or that,’” she said. Instead, she said, the agency highlights unusual issues in the data, allowing economists and other observers to adjust the numbers as they see fit.

“That’s part of the transparency that they’ve built into the process,” she said.

Are there other issues with the jobs numbers?

The pandemic has made it more difficult for the government to reach households and businesses to conduct surveys, in part because in-person interviews are suspended. The response rate in the survey of households was 67 percent in May, compared with 83 percent in February, before most of the pandemic-related shutdowns.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics said it was “still able to obtain estimates that met our standards for accuracy and reliability,” but economists say the numbers may be less reliable than usual.

Virus-related disruptions could skew the data in other ways. They have thrown off typical seasonal patterns of hiring and firing, which are ordinarily factored into the results, and have scrambled usual assumptions about how many businesses are being formed or shutting down permanently.

How could economists have gotten it so wrong?

Economists overwhelmingly expected Friday’s report to show a loss of jobs and an increase in the unemployment rate. But that shouldn’t necessarily sow suspicion.

For one thing, economists are notoriously bad at predicting turning points in the economy. They didn’t see the 2008-9 recession coming until it had begun.

In this case, economists thought that job losses continued in May largely because millions of people were filing for unemployment benefits. The data released on Friday agreed: It showed that job losses were elevated in May.

But what unemployment claims didn’t capture was that a significant number of businesses were beginning to rehire workers as the economy reopened, including employers doing so to meet the terms of loans received under the federal Payroll Protection Program. That rehiring went undetected in part because employers didn’t have to post the jobs publicly — they just had to call back workers from layoff or furlough.

“The numbers are real — I just think we got blindsided because we got too focused on claims,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. He noted that data from private sources, such as air travel and restaurant bookings, began to improve in mid-April, which is consistent with the modest rebound shown in the jobs report.

How do we know the numbers aren’t rigged?

This isn’t the first time that prominent people have questioned the jobs numbers. In 2012, Jack Welch, the former General Electric chief, implied that “Chicago guys” in the Obama administration had rigged a jobs report to help the president win re-election. As a presidential candidate in 2016, Donald Trump called the unemployment rate, then at 5 percent, “one of the biggest hoaxes in American modern politics.”

But as my colleague Patricia Cohen wrote at the time, there are many protections in place to ensure that the jobs numbers and other economic indicators are kept free of politics. And Ms. Groshen and other economists said they had seen no evidence that has changed under Mr. Trump.

“I have seen no red flags, anything to suggest that the numbers are rigged,” Ms. Groshen said. The Bureau of Labor Statistics is headed by a political appointee, currently William W. Beach, who previously served as a Republican Senate staff member and an economist at the conservative Heritage Foundation. But the rest of the bureau is staffed by career employees, many predating the Trump administration.

Ms. Groshen and other economists say those employees, whom she called “the most dedicated data nerds on the face of the earth,” would raise alarms if they saw signs of political interference. And there is virtually no way the numbers could be changed without their noticing, she said. Source: paper.li

Comments