Researchers produce gadgets such as gastric balloons that break down when lit by swallowable lights

The approach could be extended to a broader range of medical equipment

The days of needing to have medical devices removed through an invasive procedure could be numbered. Researchers have produced gadgets such as gastric balloons that break down when light from a swallowable LED shines upon them.

The team say the approach could be extended to a broader range of medical equipment, as well as offering a new approach to delivering drugs to the right location at the right time.

“We have the ability to control when those devices break up through the application of light,” said Giovanni Traverso, co-author of the study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s hospital in the US.

At the heart of the approach is a hydrogel – a squishy, water-absorbing material made of polymers.

“You can imagine that if you put something really stiff and heavy and rigid inside your body, the rest of your tissues– which are quite soft by comparison– may have a negative reaction to that,” said Ritu Raman, first author of the research who is also from MIT.

However, hydrogels can be tweaked to make them stiffer or stretchier, while it is also possible to engineer them so they break down in certain environments, for example by exposure to acidity or heat.

The team said they chose to use light since it was easy to control and could be used across different environments in the body, while the wavelength could be selected so it did not harm surrounding tissues.

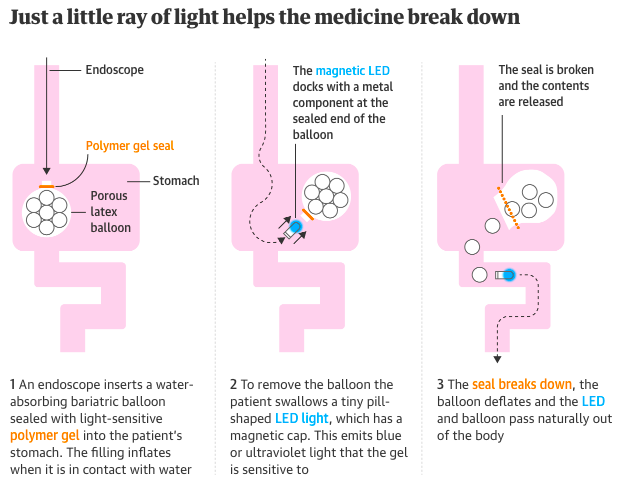

Writing in the journal Science Advances, Traverso and colleagues report how they applied their approach to gastric balloons – devices that aid weight loss by making a patient feel fuller. These are typically inserted into the stomach, inflated with a fluid and removed up to six months later – often with an endoscope.

Rather than filling the balloon with fluid, the team filled the porous shell with a material that rapidly inflates when wet, and sealed it with a pin made from their specially designed light-responsive hydrogel.

An hour after inserting the gastric balloons into the stomach of three pigs and checking they had inflated, the team passed an endoscope bearing an LED into each pig and shone light onto the hydrogel pin for 30 minutes.

Six hours after the balloon was inserted scans showed it had reduced to almost 70% of its original inflated size, suggesting the pin had broken down and the balloon’s contents released. By contrast, gastric balloons in three pigs that had not been exposed to an internal LED had continued to inflate.

The team found similar results could be produced by inserting an ingestible LED capsule into another three pigs. This was switched on for at least 70 minutes.

Both the LED endoscope and LED capsule contained a small magnet to guide it to a metallic piece near the pin of the gastric balloon. Traverso said the magnets could be chosen for strength so they would not stick together across bodily tissue.

While the team did not show that the gastric balloon was subsequently passed by the pigs, Traverso said it was very likely it would have been, since the constituent parts were now small enough to pass from the stomach into the intestines.

The team also made sections of a ring-shaped stent for the oesophagus out of the hydrogel, although this was not tested in live animals. After exposure to LEDs for 30 minutes, the stent became far squishier, with tests suggesting it would be able to pass into the stomach and out of the body. Traditionally such stents have to be removed by an endoscope.

Traverso said the study was a proof of concept and further work was needed – such as developing an approach that did not involve the LED attaching to the device. However the team was hopeful that the approach could eventually aid patients in a range of ways, including for controlling the release of drugs in the body.

Prof Mark Miodownik, a materials engineer at University College London who was not involved in the research, said the approach was a really good example of “animate” materials, adding that while light-degrading materials had been produced before, the new study showed a well-controlled trigger, a carefully tuned hydrogel fit for use in the body, and suggested the device and LED capsule could subsequently pass out of the body.

He said: “This [provides] a whole new set of possibilities for non-invasive surgery where you put stuff in the body and when it has done its job you send a little [LED] pill down. I think the next stage is probably to send the self-destruct [mechanism] with [the device] in the first place.”

As 2020 begins…

… we’re asking readers, like you, to make a new year contribution in support of the Guardian’s open, independent journalism. This has been a turbulent decade across the world – protest, populism, mass migration and the escalating climate crisis. The Guardian has been in every corner of the globe, reporting with tenacity, rigour and authority on the most critical events of our lifetimes. At a time when factual information is both scarcer and more essential than ever, we believe that each of us deserves access to accurate reporting with integrity at its heart.

More people than ever before are reading and supporting our journalism, in more than 180 countries around the world. And this is only possible because we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay.

We have upheld our editorial independence in the face of the disintegration of traditional media – with social platforms giving rise to misinformation, the seemingly unstoppable rise of big tech and independent voices being squashed by commercial ownership. The Guardian’s independence means we can set our own agenda and voice our own opinions. Our journalism is free from commercial and political bias – never influenced by billionaire owners or shareholders. This makes us different. It means we can challenge the powerful without fear and give a voice to those less heard.

None of this would have been attainable without our readers’ generosity – your financial support has meant we can keep investigating, disentangling and interrogating. It has protected our independence, which has never been so critical. We are so grateful.

As we enter a new decade, we need your support so we can keep delivering quality journalism that’s open and independent. And that is here for the long term. Every reader contribution, however big or small, is so valuable. Support The Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

SOURCE:Paper.li

Komentar