Dawn Of The Neobank: The Fintechs Trying To Kill The Corner Bank

- The Tech Platform

- Jan 31, 2020

- 9 min read

The sky is the limit,” gushes MoneyLion founder and CEO Dee Choubey as he strolls into Manhattan’s Madison Square Park, the oak and ash trees turning color in the October sunshine.

Choubey, 38, is taking a midday constitutional from MoneyLion’s cramped offices in the Flatiron District, where 65 people labor to reinvent retail banking for the app generation. He ticks off a couple businesses he looks up to—ones that have fundamentally changed the way money flows around the world—putting his ambitions for his six-year-old startup into sharp relief. “PayPal,” he says. “Square.” Two companies worth a combined $150 billion.

“The promise of MoneyLion is to be the wealth manager, the private bank for the $50,000 household,” Choubey says.

At last count, MoneyLion’s app had 5.7 million users, up from 3 million a year ago, and a million of those are paying customers. Those people, many from places like Texas and Ohio, fork over $20 per month to maintain a MoneyLion checking account, monitor their credit score or get a small low-interest loan. In all, MoneyLion offers seven financial products, including unexpected ones like paycheck advances and, soon, brokerage services. Choubey expects revenue of $90 million this year, triple last year’s $30 million. His last round of financing, when he raised $100 million from investors including Princeton, New Jersey-based Edison Partners and McLean, Virginia-based Capital One, valued the company at nearly $700 million. By mid-2020, he predicts, MoneyLion will be breaking even. An FDIC-insured high-yield savings account will be rolled out soon, while credit cards are on the schedule for later in 2020. To retain customers, he says, “we have to be a product factory.”

Like most other entrepreneurs, Choubey thinks his company’s potential is essentially unlimited. But having spent a decade as an itinerant investment banker at Citi, Goldman, Citadel and Barclays, he’s also a guy who knows how far a horizon can realistically stretch. And he is far from the only one to see the opportunity for upstart digital-only banks—so-called neobanks—to transform retail banking and create a new generation of Morgans and Mellons. “I just heard a rumor that Chime is getting another round at a $5 billion valuation,” he says.

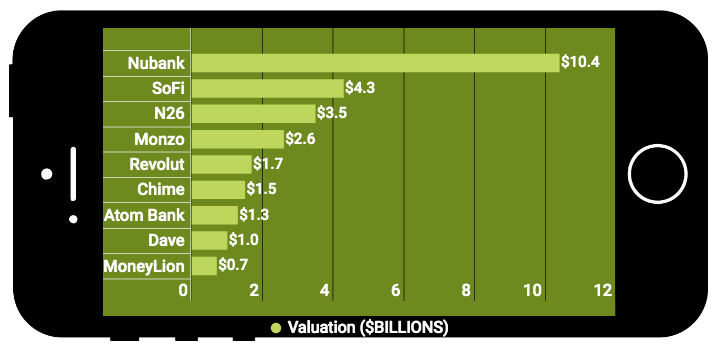

Leading the Neobank Pack

In 20 years, these VC-backed startups could dominate consumer banking, but they’ll face plenty of competition. Fintech companies that originally offered investing are rushing to add bank services.

Sources: the companies, CB Insights, PitchBook.

Globally, a vast army of neobanks are targeting all sorts of consumer and small-business niches—from Millennial investors to dentists and franchise owners. McKinsey estimates there are 5,000 startups worldwide offering new and traditional financial services, up from 2,000 just three years ago. In the first nine months of 2019, venture capitalists poured $2.9 billion into neobanks, compared with $2.3 billion in all of 2018, reports CB Insights.

Underlying this explosion is new infrastructure that makes starting a neobank cheap and easy, plus a rising generation that prefers to do everything from their phones. While it can take years and millions in legal and other costs to launch a real bank, new plug-and-play applications enable a startup to hook up to products supplied by traditional banks and launch with as little as $500,000 in capital.

“Now you can get your [fintech] company off the ground in a matter of a few months versus a few years,” says Angela Strange, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, who sits on the board of Synapse, a San Francisco-based startup whose technology makes it easier for other startups to offer bank products.

Using such middleman platforms, tiny neobanks can offer big-bank products: savings accounts insured by the FDIC, checking accounts with debit cards, ATM access, credit cards, currency transactions and even paper checks. That frees fintech entrepreneurs to concentrate on cultivating their niche, no matter how small or quirky.

Take “Dave.” Dave (yep, that’s its real name) is a little app that rescues folks from the pain of chronic bank overdraft fees. Created by a 34-year-old serial entrepreneur named Jason Wilk who had no prior experience in financial services, Dave charges its users $1 a month and, if they seem likely to overdraw, instantly deposits up to $75 as an advance. Nice little business, but nothing to give Bank of America jitters.

Betterment cofounder Jon Stein at his New York City startup. It took a decade to get 420,000 clients for its robo-advisor business managing stocks and bonds; as a neobank newcomer, Betterment already has 120,000 on a waiting list for a checking account.

But then Wilk decided to turn Dave into a neobank. In June, using Synapse, Dave rolled out its own checking account and debit card. Now it can make money on “interchange,” the 1% to 2% fees that retailers get charged whenever a debit card gets swiped. These fees are split between banks and debit-card issuers like Dave. Wilk optimistically predicts Dave will bring in $100 million in revenue this year from its 4.5 million users—up from $19 million in 2018, the year before it transformed itself into a neobank. Dave was recently valued at $1 billion.

Established fintech companies that didn’t start out in banking are getting into the game too. New York-based Betterment, which manages $18 billion in customers’ stock and bond investments using computer algorithms, recently rolled out a high-yield savings account. It pulled in $1 billion in deposits in two weeks. “The success has been unprecedented. In our history we’ve never grown this fast,” marvels Betterment CEO and cofounder Jon Stein. Now he’s launching a no-fee checking account with a debit card, and credit cards and mortgages might be next, he says.

Neobanks are swiftly emerging as a huge threat to traditional banks. McKinsey estimates that by 2025 up to 40% of banks’ collective revenue could be at risk from new digital competition. “I don’t believe there’s going to be a Netflix moment—where Netflix basically leapfrogs Blockbuster—where fintechs basically put the banks out of business,” says Nigel Morris, a managing partner at QED Investors, an Alexandria, Virginia-based VC firm specializing in fintech. “[Traditional banks] are really complicated businesses, with complex regulatory issues and consumers who are relatively inert.” But, he adds, “If [neobanks] can get people to bundle, [they] can get more of a share of a wallet of a consumer. [The] economics can move dramatically. It changes the game.”

Diwakar (Dee) Choubey was supposed to be an engineer, not an investment banker. Born in Ranchi, India, he came to the U.S. at 4 when his father was finishing a graduate degree in engineering at Syracuse University. The family ended up in New Jersey. Choubey’s mom taught autistic children, while his dad worked as an engineer at Cisco—and plotted his son’s future.

When Choubey started at the University of Chicago in 1999, he signed up for a bunch of computer science classes picked by his dad. But after earning a couple of B-minuses, “I cried uncle,” Choubey says. He became an economics major, strengthening his grades and job prospects by taking corporate finance and accounting courses at the business school. After graduating with honors, he went into investment banking, where he remained for the next decade.

MoneyLion founder Dee Choubey in his Manhattan offices. “We’ve built one piece of technology that’s part bank, part personal-finance manager, part broker-dealer and part lender.”

From an insider’s vantage point, he saw that traditional banks were excruciatingly slow to respond to the preferences of their customers and exploit the power of smartphones. That, plus a never-ending series of bank scandals, convinced him that there was an opening for a digital “private banker.” In 2013 he walked away from his near-seven-figure salary to start MoneyLion.

Choubey raised $1 million in seed funding and started out offering free credit scores and micro-loans. But he struggled to raise more money. Forty venture investors turned him down, deeming his vision impractical and unfocused. “I was laughed out of a lot of VC rooms in our early days,” he recalls.

While Choubey banged unsuccessfully on VC doors, MoneyLion putt-putted along, bringing in a little revenue from loan interest and credit card ads and collecting a bunch of data on consumer behavior. Finally, in 2016, he persuaded Edison Partners to lead a $23 million investment. That enabled MoneyLion to add a robo-advisor service allowing users to invest as little as $50 in portfolios of stocks and bonds. In 2018, it added a free checking account and debit card issued through Iowa-based Lincoln Savings Bank.

Managing rapid growth, while striving to keep costs low, has proved tricky. MoneyLion was hit with a deluge of Better Business Bureau complaints over the past spring and summer. Some customers experienced long delays transferring their money into or out of MoneyLion accounts and, when they reached out for help, got only computer-generated responses. Choubey says the software glitches have been fixed, and he has bumped up the number of customer-service reps from 140 to 230.

Other neobanks have had operational growing pains too. In October, San Francisco-based Chime, with 5 million accounts, had technical problems that stretched over three days. Customers were unable to see their balances, and some were intermittently unable to use their debit cards. Chime blamed the failure on a partner, Galileo Financial Technologies, a platform used by many fintech startups to process transactions.

Tim Spence, Fifth Third’s chief strategist, in the regional bank’s downtown Cincinnati headquarters. Most of his neobank competitors are losing money, but “the lesson . . . learned from Facebook and Amazon and Google . . . is that the internet is amenable to a winner-take-all market structure.”

On a warm fall day Tim Spence speed-walks his 6-foot-3 frame through the towering, 31-story Cincinnati headquarters of his employer, Fifth Third, a 161-year-old regional bank with $171 billion in assets. Clad in a plaid sport jacket with no tie, Spence doesn’t look like a traditional banker. And he’s not.

A Colgate University English literature and economics major, Spence, now 40, spent the first seven years of his career at digital advertising startups. He then moved into consulting at Oliver Wyman in New York, advising banks on digital transformation. In 2015, Fifth Third lured him to Ohio as its chief strategy officer and then expanded his mandate. He now also oversees consumer banking and payments, putting him in charge of $3 billion worth of Fifth Third’s $6.9 billion in revenue. Last year, he brought home $3 million in total compensation, making him the bank’s fourth-highest-paid executive.

Fifth Third has 1,143 branches, but today Spence is focused on Dobot, a mobile app the bank acquired in 2018 and relaunched this year. Dobot helps users set personalized savings goals and automatically shifts money from checking to savings accounts. “We reached 80,000 downloads in a matter of six months, without having to spend hardly anything on marketing,” he says.

Scooping up new products is one part of a three-pronged “buy-partner-build” strategy that Spence has helped devise to combat the neobank challenge. Partnering means both investing in fintechs and funding loans generated by the newcomers. Fifth Third has a broad deal with Morris’ QED, which gives it a chance to invest in the startups the VC firm backs. One of Fifth Third’s earliest QED investments was in GreenSky, the Atlanta-based fintech that generates home remodeling loans (some funded by Fifth Third) through a network of general contractors.

The best of these partnerships provide Fifth Third access to younger borrowers, particularly those with high incomes. In 2018, it led a $50 million investment in New York-based CommonBond, which offers student-loan refinancing to graduates at competitive interest rates. Similarly, Fifth Third has invested in two San Francisco-based startups: Lendeavor, an online platform that makes big loans to young dentists opening new private practices, and ApplePie Capital, which lends money to fast-food franchisees.

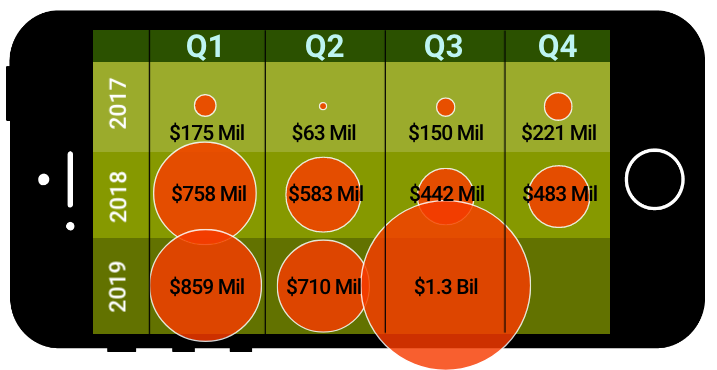

Funding Bonanza

Global venture capital funding for digital banks is exploding. This year, it’s on pace to exceed 2017 and 2018 combined.

Source: CB Insights

“The thing I’m most envious of, when it comes to the venture-backed startups that we compete with, is the quality of talent they’re able to bring in. It’s really remarkable,” Spence says.

But while Spence envies them sometimes and partners where he can, he isn’t convinced the neobanks will make big inroads into traditional banks’ turf. “None of them have shown that they can take over primary banking,” he says. He also argues that having physical retail branches is still important for building long-term relationships with customers. In a recent Javelin survey of 11,500 consumers, an equal number rated online capabilities and branch convenience as the most important factors when deciding whether to stick with a bank.

Fifth Third has been reducing its overall number of branches an average of 3% a year, but it’s opening new ones designed to be Millennial-friendly. These outlets are just two thirds the size of traditional branches. Instead of snaking teller lines, there are service bars and meeting areas with couches. Bankers armed with tablets greet customers at the door—Apple Store-style.

That raises the question of whether any of the neobanks will be so successful that they’ll eventually open physical outposts, the way internet retailers Warby Parker, Casper and, of course, Amazon have done. After all, it’s happened before. Capital One pioneered the use of big data to sell credit cards in the early 1990s, making it one of the first successful fintechs. But in 2005 it started acquiring traditional banks, and today it’s the nation’s tenth-largest bank, with $379 billion in assets and 480 branches.

SOURCE:Paper.li

Comments